Friday, January 30, 2009

Then and Now: Northeast corner of rue du Bac and boulevard St-Germain, Paris

The intersection of rue du Bac and the boulevards St-Germain and Raspail was once home to a small square with a statue of Claude Chappe, inventor of the electric telegraph's predecessor, as its focal point. The statue was destroyed during by the Nazis during the Occupation and evidently never replaced. Rue du Bac also seems to have been widened.

Original Photo: "ND-3815 Rés." Collection Roger-Viollet. Parisenimages.fr. Parisienne de Photographie. 28 Jan. 2009. http://www.parisenimages.fr/Export450/13000/12127-11.jpg

Tuesday, January 27, 2009

Thoughts on the Shirt Corner

Another page turns for Old City Philadelphia. Michael Klein at the Insider reported a week ago that the Shirt Corner, the landmark business at the northeast corner of 3rd and Market, would be closing shortly as its owner is entering retirement. At the time, Phoodie floated the unpleasant rumor that the long-time bastion of Old City's pre-gentrification era businesses could be replaced by none other than a decidedly un-hip Applebee's outpost. However, it looks like the truth may be much worse, as Inga Saffron reports in today's Inquirer.

Okay, so the Shirt Corner's buildings aren't very pretty. Even in their original, unaltered state, they would have none of the height, vast windows, or cast-iron flair of the late-19th century commercial and manufacturing buildings that Old City is known for. But a brief stroll in the neighborhood (or on Google Street View) should tell you that the district has just as many or perhaps more non-descript brick buildings standing around that in effect contribute no less to its lively and eclectic streetscape, and are no less part of its architectural heritage.

Thus, I find Farnham's statement rather alarming. During its urban renewal days, neighboring Society Hill lost plenty of its Victorian-era architecture to liberal destruction of buildings deemed "not key to the district's character." This strange desire for homogeneity in historic districts is all too common, and when acted upon, always tends to create overly artificial and somewhat sanitized neighborhoods. Plain as the buildings in question are, they testify honestly to Old City's industrial 19th-century history.

In addition, remnants of this era have unfortunately fared very badly elsewhere on Market Street. The north half of the 100 block was entirely demolished in the construction of Penn's Landing, as was a good portion everything between 3rd and 5th, including the entire 400 block. Market Street in Old City by no means needs to lose any more of its 19th-century buildings than it already has. Lastly, historical replicas seem more often than not to be done rather poorly, and I am highly wary of the possibility of seeing one here.

I'm sure that the buildings will not be simple to readapt, but I can't bring myself to accept demolition as an answer. What is to prevent the developer from demolishing the buildings and failing to follow through with construction plans? Will we perhaps get a nice surface parking lot? It's hardly out of the question in this economic climate. I say it's a risk that Philadelphia simply cannot afford to take.

Shirt Corner closing, site's future in play [Philadelphia Inquirer]

Although the properties remain in the hands of the Shirt Corner's 77-year-old owner, Marvin Ginsberg, a potential buyer is scheduled to appear today before a Historical Commission subcommittee to request permission to tear down the row of mid-19th-century structures.Though the request today will likely be denied since the buyer, Avi Nechemia, has failed to submit all required documentation, things might not stay that way for long...

Were Nechemia to supply the information, there are indications that the demolition could eventually win approval from the commission. In its one-page analysis, the Historical Commission's advisory staff pointedly noted that "this application has some merit."Historical Commission Executive Director Jonathan Farnham doesn't seem to see particular importance in the existing structures either, claiming that they "themselves are not key to the district's character."

...Though the plan involves tearing out a big chunk of Market Street's original commercial fabric, Nechemia is promising to replace the lost buildings with a faithful replica that disguises a modern interior.

Okay, so the Shirt Corner's buildings aren't very pretty. Even in their original, unaltered state, they would have none of the height, vast windows, or cast-iron flair of the late-19th century commercial and manufacturing buildings that Old City is known for. But a brief stroll in the neighborhood (or on Google Street View) should tell you that the district has just as many or perhaps more non-descript brick buildings standing around that in effect contribute no less to its lively and eclectic streetscape, and are no less part of its architectural heritage.

Thus, I find Farnham's statement rather alarming. During its urban renewal days, neighboring Society Hill lost plenty of its Victorian-era architecture to liberal destruction of buildings deemed "not key to the district's character." This strange desire for homogeneity in historic districts is all too common, and when acted upon, always tends to create overly artificial and somewhat sanitized neighborhoods. Plain as the buildings in question are, they testify honestly to Old City's industrial 19th-century history.

In addition, remnants of this era have unfortunately fared very badly elsewhere on Market Street. The north half of the 100 block was entirely demolished in the construction of Penn's Landing, as was a good portion everything between 3rd and 5th, including the entire 400 block. Market Street in Old City by no means needs to lose any more of its 19th-century buildings than it already has. Lastly, historical replicas seem more often than not to be done rather poorly, and I am highly wary of the possibility of seeing one here.

I'm sure that the buildings will not be simple to readapt, but I can't bring myself to accept demolition as an answer. What is to prevent the developer from demolishing the buildings and failing to follow through with construction plans? Will we perhaps get a nice surface parking lot? It's hardly out of the question in this economic climate. I say it's a risk that Philadelphia simply cannot afford to take.

Shirt Corner closing, site's future in play [Philadelphia Inquirer]

Monday, January 26, 2009

Happy New Year!

Happy Chinese New Year, that is. Unfortunately, it's been much like any other Monday in Paris, and it has been years since I have had the fortune of properly celebrating the lunar new year back in Taiwan. Consequently I don't have any related pictures, though I felt compelled to upload the one above, taken last summer on one of many late afternoon bike rides in Neihu. Fortunately, those of us in the northern hemisphere can all be well assured of warmer and brighter days come springtime, whatever else the year will bring. Best wishes for the new year!

Happy Chinese New Year, that is. Unfortunately, it's been much like any other Monday in Paris, and it has been years since I have had the fortune of properly celebrating the lunar new year back in Taiwan. Consequently I don't have any related pictures, though I felt compelled to upload the one above, taken last summer on one of many late afternoon bike rides in Neihu. Fortunately, those of us in the northern hemisphere can all be well assured of warmer and brighter days come springtime, whatever else the year will bring. Best wishes for the new year!

Sunday, January 25, 2009

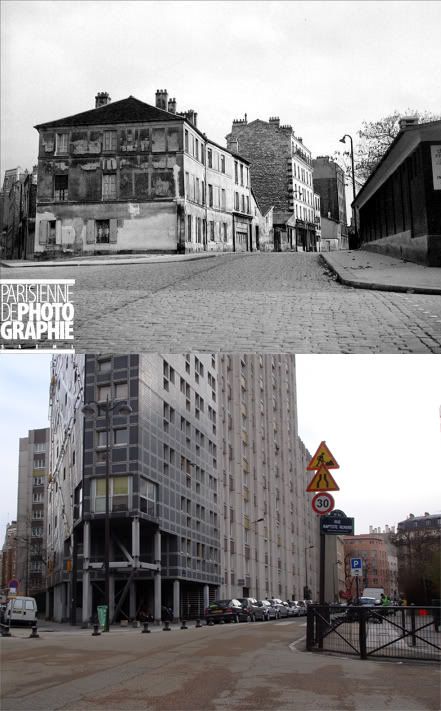

Then and Now: Rue du Château des Rentiers towards rue de Tolbiac, Paris

19xx-2009

19xx-2009Like many streets of Paris' 13th arrondissement, the rue du Château des Rentiers was nearly entirely rebuilt in the 60s and 70s as part of a massive urban renewal effort.

Original photo: "Paris (13ème arr.). Rue Château des Rentiers." Collection Roger-Viollet. Parisenimages.fr. Parisienne de Photographie. 24 Jan. 2009. http://www.parisenimages.fr/Export450/1000/680-3.jpg

Friday, January 23, 2009

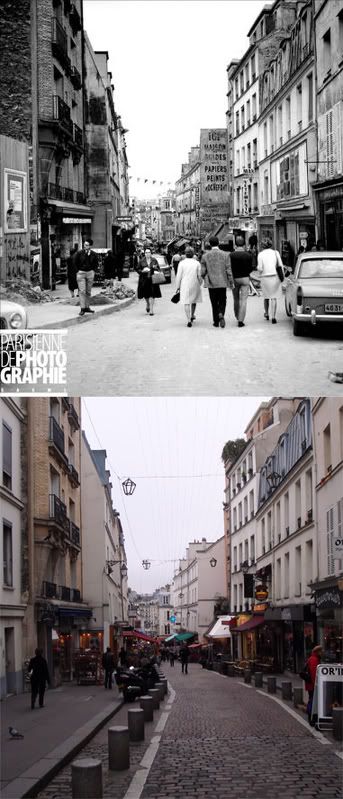

Then and Now: Rue Mouffetard south of Rue de l'Epée de Bois, Paris

1968-2009

1968-2009Original photo: "RV-202390." 1968. Collection Roger-Viollet. Parisenimages.fr. Parisienne de Photographie. 21 Jan. 2008. http://www.parisenimages.fr/Export450/4000/3600-10.jpg

Wednesday, January 21, 2009

Then and Now: 31st and Market looking west, Philadelphia

Today, the 3100 block of Market Street is occupied entirely by Drexel University, though one building from the original photo still stands. The Frank Furness designed Centennial National Bank at 32nd and Market now houses the University's Paul Peck Alumni Center.

Original Photo: "Public Works-1404-0." 1881. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 18 Dec. 2008. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=103173

Sunday, January 18, 2009

Paris Rive Gauche

I have made several visits in the past week to Paris Rive Gauche, an area not to be confused with the older part of town traditionally referred to as the Left Bank. Rive Gauche is a massive urban redevelopment project occupying the 13th arrondissement along the banks of the Seine, in a former industrial zone cut off from the city by the railroad tracks of the Gare d'Austerlitz.

Having fallen largely into abandonment by the 1980s, the area became the focus of a large urban rewewal effort led by a semi-municipal authority called SEMAPA (Société d'économie mixte d'aménagement de Paris), which sought to reconnect the 13th arrondissement to its riverfront via the creation of an entirely new city neighborhood. The area is best known as the site of the Bibliothèque François Mitterrand, the gargantuan central branch of the national library system, opened in 1996.

Having fallen largely into abandonment by the 1980s, the area became the focus of a large urban rewewal effort led by a semi-municipal authority called SEMAPA (Société d'économie mixte d'aménagement de Paris), which sought to reconnect the 13th arrondissement to its riverfront via the creation of an entirely new city neighborhood. The area is best known as the site of the Bibliothèque François Mitterrand, the gargantuan central branch of the national library system, opened in 1996.

Enormous and controversial as the library complex is, it is actually the other parts of the quarter that have been of particular interest to me. Upon descending from the seemingly endless wooden terrace of the library complex, one finds streets of a scale very similar to that of Paris' older neighborhoods, apart from their apparent grid layout.

Enormous and controversial as the library complex is, it is actually the other parts of the quarter that have been of particular interest to me. Upon descending from the seemingly endless wooden terrace of the library complex, one finds streets of a scale very similar to that of Paris' older neighborhoods, apart from their apparent grid layout.

Quite unlike the rest of Paris however, the vast majority of buildings in the area was built within the past decade, creating perhaps the highest concentration of contemporary architecture to be found in the city. A continuous work in progress, Rive Gauche has served as a playground for some of France's most reknown contemporary architects, working from an eclectic palette of styles.

Quite unlike the rest of Paris however, the vast majority of buildings in the area was built within the past decade, creating perhaps the highest concentration of contemporary architecture to be found in the city. A continuous work in progress, Rive Gauche has served as a playground for some of France's most reknown contemporary architects, working from an eclectic palette of styles.

Equally fascinating is the enormous diversity of uses to be found here. Rive Gauche is already home to classroom and administrative buildings of several universities, numerous residential buildings, commercial and government offices, and a large MK2 cinema complex. It's a great example of a truly mixed-use neighborhood that has come out of a comprehensive and well-executed plan on the part of SEMAPA.

Equally fascinating is the enormous diversity of uses to be found here. Rive Gauche is already home to classroom and administrative buildings of several universities, numerous residential buildings, commercial and government offices, and a large MK2 cinema complex. It's a great example of a truly mixed-use neighborhood that has come out of a comprehensive and well-executed plan on the part of SEMAPA.

Work continues on removing the physical barrier presented by the railroad tracks, which still separates Rive Gauche from older neighborhoods to the west. A portion of the tracks has already been built over, and more elevated buildings are currently under construction above them.

Work continues on removing the physical barrier presented by the railroad tracks, which still separates Rive Gauche from older neighborhoods to the west. A portion of the tracks has already been built over, and more elevated buildings are currently under construction above them.

The development of Paris Rive Gauche should provide important insight and inspiration for planners working on Philadelphia's Delaware waterfront plan. The initial problem, reconnecting the postindustrial city to its river, is the same. Granted, I-95 and its interchanges present a much greater barrier than a set of railroad tracks. Nonetheless, there is clear proof that the creation of a successful city neighborhood can be done with the right public investment.

The development of Paris Rive Gauche should provide important insight and inspiration for planners working on Philadelphia's Delaware waterfront plan. The initial problem, reconnecting the postindustrial city to its river, is the same. Granted, I-95 and its interchanges present a much greater barrier than a set of railroad tracks. Nonetheless, there is clear proof that the creation of a successful city neighborhood can be done with the right public investment.

Most importantly, Rive Gauche owes its success to crucial parternships between planners, government and educational institutions, and private developers. Nearly all institutions, public and private, seek to expand or find new digs at one point or another. Just imagine the momentum that Philadelphia's waterfront plan would gain if one of its ever-growing universities, Penn, Drexel, or Temple, took a stake in waterfront property. This kind of development is nothing new to Philadelphia - Independence Mall was created by a similarly far-reaching enterprise that created Rohm and Haas' headquarters, the James A. Byrne federal courthouse, and US Mint building, among others.

Most importantly, Rive Gauche owes its success to crucial parternships between planners, government and educational institutions, and private developers. Nearly all institutions, public and private, seek to expand or find new digs at one point or another. Just imagine the momentum that Philadelphia's waterfront plan would gain if one of its ever-growing universities, Penn, Drexel, or Temple, took a stake in waterfront property. This kind of development is nothing new to Philadelphia - Independence Mall was created by a similarly far-reaching enterprise that created Rohm and Haas' headquarters, the James A. Byrne federal courthouse, and US Mint building, among others.

Having fallen largely into abandonment by the 1980s, the area became the focus of a large urban rewewal effort led by a semi-municipal authority called SEMAPA (Société d'économie mixte d'aménagement de Paris), which sought to reconnect the 13th arrondissement to its riverfront via the creation of an entirely new city neighborhood. The area is best known as the site of the Bibliothèque François Mitterrand, the gargantuan central branch of the national library system, opened in 1996.

Having fallen largely into abandonment by the 1980s, the area became the focus of a large urban rewewal effort led by a semi-municipal authority called SEMAPA (Société d'économie mixte d'aménagement de Paris), which sought to reconnect the 13th arrondissement to its riverfront via the creation of an entirely new city neighborhood. The area is best known as the site of the Bibliothèque François Mitterrand, the gargantuan central branch of the national library system, opened in 1996. Enormous and controversial as the library complex is, it is actually the other parts of the quarter that have been of particular interest to me. Upon descending from the seemingly endless wooden terrace of the library complex, one finds streets of a scale very similar to that of Paris' older neighborhoods, apart from their apparent grid layout.

Enormous and controversial as the library complex is, it is actually the other parts of the quarter that have been of particular interest to me. Upon descending from the seemingly endless wooden terrace of the library complex, one finds streets of a scale very similar to that of Paris' older neighborhoods, apart from their apparent grid layout. Quite unlike the rest of Paris however, the vast majority of buildings in the area was built within the past decade, creating perhaps the highest concentration of contemporary architecture to be found in the city. A continuous work in progress, Rive Gauche has served as a playground for some of France's most reknown contemporary architects, working from an eclectic palette of styles.

Quite unlike the rest of Paris however, the vast majority of buildings in the area was built within the past decade, creating perhaps the highest concentration of contemporary architecture to be found in the city. A continuous work in progress, Rive Gauche has served as a playground for some of France's most reknown contemporary architects, working from an eclectic palette of styles. Equally fascinating is the enormous diversity of uses to be found here. Rive Gauche is already home to classroom and administrative buildings of several universities, numerous residential buildings, commercial and government offices, and a large MK2 cinema complex. It's a great example of a truly mixed-use neighborhood that has come out of a comprehensive and well-executed plan on the part of SEMAPA.

Equally fascinating is the enormous diversity of uses to be found here. Rive Gauche is already home to classroom and administrative buildings of several universities, numerous residential buildings, commercial and government offices, and a large MK2 cinema complex. It's a great example of a truly mixed-use neighborhood that has come out of a comprehensive and well-executed plan on the part of SEMAPA. Work continues on removing the physical barrier presented by the railroad tracks, which still separates Rive Gauche from older neighborhoods to the west. A portion of the tracks has already been built over, and more elevated buildings are currently under construction above them.

Work continues on removing the physical barrier presented by the railroad tracks, which still separates Rive Gauche from older neighborhoods to the west. A portion of the tracks has already been built over, and more elevated buildings are currently under construction above them. The development of Paris Rive Gauche should provide important insight and inspiration for planners working on Philadelphia's Delaware waterfront plan. The initial problem, reconnecting the postindustrial city to its river, is the same. Granted, I-95 and its interchanges present a much greater barrier than a set of railroad tracks. Nonetheless, there is clear proof that the creation of a successful city neighborhood can be done with the right public investment.

The development of Paris Rive Gauche should provide important insight and inspiration for planners working on Philadelphia's Delaware waterfront plan. The initial problem, reconnecting the postindustrial city to its river, is the same. Granted, I-95 and its interchanges present a much greater barrier than a set of railroad tracks. Nonetheless, there is clear proof that the creation of a successful city neighborhood can be done with the right public investment. Most importantly, Rive Gauche owes its success to crucial parternships between planners, government and educational institutions, and private developers. Nearly all institutions, public and private, seek to expand or find new digs at one point or another. Just imagine the momentum that Philadelphia's waterfront plan would gain if one of its ever-growing universities, Penn, Drexel, or Temple, took a stake in waterfront property. This kind of development is nothing new to Philadelphia - Independence Mall was created by a similarly far-reaching enterprise that created Rohm and Haas' headquarters, the James A. Byrne federal courthouse, and US Mint building, among others.

Most importantly, Rive Gauche owes its success to crucial parternships between planners, government and educational institutions, and private developers. Nearly all institutions, public and private, seek to expand or find new digs at one point or another. Just imagine the momentum that Philadelphia's waterfront plan would gain if one of its ever-growing universities, Penn, Drexel, or Temple, took a stake in waterfront property. This kind of development is nothing new to Philadelphia - Independence Mall was created by a similarly far-reaching enterprise that created Rohm and Haas' headquarters, the James A. Byrne federal courthouse, and US Mint building, among others.

Friday, January 16, 2009

Then and Now: Rue de Fleurus towards Rue d'Assas, Paris

La Rue de Fleurus runs out of the western edge of the Jardin du Luxembourg and is home in part to the Alliance Française and the many students that attend its courses. It's hard to picture the quiet street today as having at one point been the front line of one of mankind's most brutal wars. Equally stunning is the fact that all of the buildings in the photo survived the events pictured.

Original Photo: "ND-166013." 1944. Collection Roger-Viollet. Parisenimages.fr. Parisienne de Photographie. 13 Jan. 2009. http://www.parisenimages.fr/Export450/3000/2164-6.jpg

Tuesday, January 13, 2009

Then and Now: Passage du Moulin-des-Prés, Paris

Original photo: "RV-759748." 1944-1945. Collection Roger-Viollet. Parisenimages.fr. Parisienne de Photographie. 12 Jan. 2009. http://www.parisenimages.fr/Export450/2000/1427-3.jpg

Monday, January 12, 2009

Hancock Square, Northern Liberties, Philadelphia

Of the many projects born from Philadelphia's recent boom in high-end residential construction, Hancock Square in Northern Liberties is easily my favorite. The development, led by Tower Investments and designed by Erdy-McHenry Architects, replaces one of several large empty lots left over from the demolition of the Schmidt's brewery. The first phase, a 6-story building along North 2nd Street was completed a few years ago. Phase two, to be completed in the coming months, includes two 7-story residential buildings on the other side of the block along Hancock Street and Germantown Avenue, a 7-story office tower, and a public plaza in between.

Of the many projects born from Philadelphia's recent boom in high-end residential construction, Hancock Square in Northern Liberties is easily my favorite. The development, led by Tower Investments and designed by Erdy-McHenry Architects, replaces one of several large empty lots left over from the demolition of the Schmidt's brewery. The first phase, a 6-story building along North 2nd Street was completed a few years ago. Phase two, to be completed in the coming months, includes two 7-story residential buildings on the other side of the block along Hancock Street and Germantown Avenue, a 7-story office tower, and a public plaza in between. The first building itself (pictured at top) is already easily the most iconic of any structure built in Northern Liberties in the last few decades. Steeped in Modernist chic, its colored wall panels and Mondrian-esque windows are clearly reminiscent of Le Corbusier's landmark Unite d'Habitation. Nonetheless, it does so while avoiding the great pitfalls of Modernist urban design. Each of the buildings meets the sidewalk with ample ground-floor retail space, and the courtyard plaza will be clearly visible and accessible from the street when completed.

The first building itself (pictured at top) is already easily the most iconic of any structure built in Northern Liberties in the last few decades. Steeped in Modernist chic, its colored wall panels and Mondrian-esque windows are clearly reminiscent of Le Corbusier's landmark Unite d'Habitation. Nonetheless, it does so while avoiding the great pitfalls of Modernist urban design. Each of the buildings meets the sidewalk with ample ground-floor retail space, and the courtyard plaza will be clearly visible and accessible from the street when completed. Furthermore, the ovular glass office tower promises to be just as iconic as its neighbors, and also ceritfy Hancock Square a true mixed-use development. Last but not least, the complex as a whole builds out at a perfectly "Parisian" density, which provides a welcome medium between the rowhomes and skyscrapers that for the most part characterize Philadelphia.

Furthermore, the ovular glass office tower promises to be just as iconic as its neighbors, and also ceritfy Hancock Square a true mixed-use development. Last but not least, the complex as a whole builds out at a perfectly "Parisian" density, which provides a welcome medium between the rowhomes and skyscrapers that for the most part characterize Philadelphia.(Construction photos were taken in late-december)

Photo credit, top photo: Timothy Hursley for Architectural Record feature. http://archrecord.construction.com/projects/bts/archives/multifamhousing/08_NoLiHousing/slide_1.asp

Saturday, January 10, 2009

Then and Now: 406 South Street, Philadelphia

Original Image: Cuneo. "Department of Public Proerpty-38424-0." 1959. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 26 Oct. 2008. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=141039

Saturday, January 3, 2009

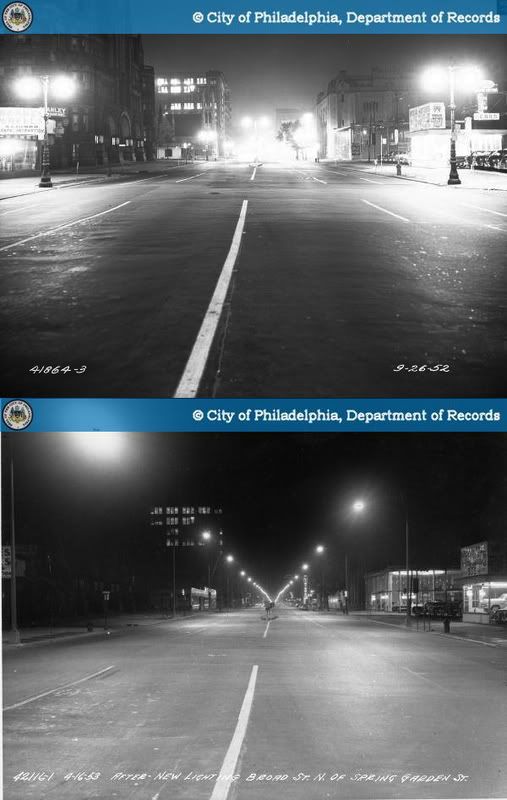

An old montage: North Broad Street north of Spring Garden, Philadelphia

Here's a before and after montage which I had no part in making, aside from a bit of photo-edited brightness correction. Taken on Broad Street north of Spring Garden, the two night photos show North Broad Street before and after the city replaced its existing street lights with the new type of fixture which has since become ubiquitous on America's streets, often called the Cobra-head light. Replicas of Broad Street's original electric street lights are still to be found on the Avenue of the Arts section of South Broad, and the Cobra-head lamps are of course still on most of North Broad Street.

It should be noted that night photography is tricky, and that its resulting photos can be slightly misleading. Nonetheless, this montage easily shows the essential fact that while Cobra-head lamps do a relatively good job of lighting the roadway, they are rather awful at lighting the sidewalk and surrounding buildings, which are barely visible in the bottom photo. I would definitely not be the first to discuss the importance of proper street lighting to pedestrian comfort and safety, so for that I would consult the archives of Philly Skyline for a great piece by contributor Nathaniel Popkin.

Though seen as nothing more than progress at the time, this replacement of street lights was in some respect the replacement of something distinctfully and gracefully Philadelphian with something banal, utilitarian, and placeless. More importantly, it reveals a planning culture that revered automobiles and highways at the expense of walking people and sidewalks. In fact, the reaction in recent decades against mid-century planning failures has been accompanied by the return of sidewalk-scaled lighting to many of America's downtowns, including most of Center City.

It's hard not to hold a somewhat morbid fascination with North Broad Street's violent decline from the grand promenade of North Philadelphia's nouveaux riches to the crumbling strip of vacant lots, gas stations, and drive-thru fast food outlets that we know today. Perhaps because of how tragic and swift that transition was, its breakdown into individual moments like these is somehow wondrous to see.

Original Photos: 1. Balionis, Francis, and Bender, Charles J. "Public Works-41864-3." 1952. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=87703

2. Bender, Charles J. "Public Works-42116-1." 1953. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 3 Jan. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=38565

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)