Sunday, December 27, 2009

Then and Now: Southwest corner of Montgomery and Anderson Avenues, Ardmore

The corner of Montgomery and Anderson Avenues was once the estate of one of Lower Merion Township's most prominent residents, Dr. George S. Gerhard, founder of Bryn Mawr Hospital. Built in the 1880s, the house was converted in the early 1920s into a residence hall for the newly consolidated Main Line YMCA, whose main building was then on Lancaster Avenue. Likely due to budget issues resulting from this arrangement, the Gerhard house was demolished and sold in early 1941. The YMCA reopened in 1956 in a new main facility across Montgomery Avenue, still used today. The former Gerhard estate has spent the last half-century as a parking lot for Suburban Square customers, sometimes referred to as "the Ruby's lot."

In 2008, the shopping center's owner, Kimco Realty, proposed replacing the lot with a mixed-use condominium complex. That suggestion was ultimately withdrawn following what seemed to be widespread opposition among nearby residents. Aside from standard concerns about height, scale, and traffic, one of their principle arguments was that development of the lot would jeopardize the planned Ardmore Transit Center. Anyhow, it's safe to say that the parking lot is here to stay for a while.

Sources:

1. Allison, Cheryl. "Abruptly, Ruby's lot plans withdrawn." Main Line Times 11 Dec. 2008.

2. "Lower Merion Atlases." Lower Merion Historical Society. 20 Dec. 2009. http://lowermerionhistory.org/atlas.html.

3. Schmidt, David. "The Main Line's YMCA has filled community needs for 95 years." Lower Merion Historical Society. 20 Dec. 2009. http://www.lowermerionhistory.org/texts/schmidtd/ymca_for_95_years.html.

4. "The first 300: The amazing and rich history of Lower Merion (part 24)." Lower Merion Historical Society. 20 Dec. 2009. http://www.lowermerionhistory.org/texts/first300/part24.html.

Original photo: "2 W. Montgomery Ave." Lower Merion/Narberth Buildings. Lowermerionhistory.org. Lower Merion Historical Society. 20 Dec. 2009. http://lowermerionhistory.org/buildings/image-building-list.php?photo_id=7420.

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

Then and Now: The Mercantile Library, 1021 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia

In 1954, ten years after joining Philadelphia's Free Library system, the Mercantile Library moved to Chestnut Street into a new building designed by local firm Martin, Stewart & Noble. The building immediately won widespread praise among the city's architectural community; Martin, Stewart & Noble were awarded 1954's Gold Medal from the Philadelphia chapter of the American Institute of Architects. Their design was acclaimed for having fulfilled the library's needs within a compact, storefront-sized space, and for its innovative adaptation of commercial design elements. The clean lines of its steel mullions, smooth glass facade, and distinctive signage make it a particularly elegant specimen of postwar Modernism in Philadelphia.

Sadly, after decades of shrinking tax revenues, the City of Philadelphia gradually became incapable of maintaining many of its facilities, including this one. The Mercantile Library shut its doors in 1989 due to a crumbling asbestos problem, and its collections were transferred to the Free Library's main branch on the Parkway. Due to daunting projected repair costs and an enormous maintenance backlog, the city ultimately chose to indefinitely close the library. Though the building was added to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places in 1990, it has only continued to deteriorate, and substantial plant overgrowth is visible on its roof.

In 2004, the lot was transferred by the city to the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation, which subsequently sold it to a private developer. However, the Mercantile Library's fate remains in limbo. There do not seem to be any current plans for its redevelopment, nor any substantial push for its preservation.

Sources:

1. "Fourth Annual Endangered Properties List." Preservation Matters. Dec. 2007. http://www.preservationalliance.com/files/news/Winter2007.pdf.

2. Wiegand, Ginny. "Library could be put on shelf." Philadelphia Inquirer. 4 Aug. 1990.

3. Maryniak, Paul. "City's building cup runneth over." Philadelphia Daily News. 26 Feb. 1991.

Original image: Carollo, R. "Historic Commission-49797-0." 1962. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 14 Dec. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=108087.

Saturday, December 5, 2009

Then and Now: 16th and Ranstead Streets looking southeast, Philadelphia

The two-story office and store building at 1535 Chestnut Street was built in 1936, and originally housed a men's clothing store and steamship company office. Today its ground floor is occupied by a nail salon and Rite Aid pharmacy.

Though not a particularly a particularly ornate building to begin with, it seems that its window panels and facade cladding have been replaced over the years. In 2008, the trees and planters were installed by the Center City District on the somewhat forlorn block to coincide with the opening of the Residences at Two Liberty Place, an office-condo conversion across 16th Street, whose dropoff area is pictured in the current view.

Source: Center City District. "Keeping Center City Green and Lush: CCD Spring Planting." Press Release. 21 Apr. 2008. 5 Dec. 2009. http://www.centercityphila.org/pressroom/prelease042108.php.

Original photo: Gee, William A. "Public Works-35968-0-B." 1936. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 16 Sep. 2009.

Monday, November 23, 2009

Then and Now: West Lancaster Avenue viewed from Wyoming Avenue, Ardmore

The original photo shows the north side of Lancaster Avenue viewed from Ardmore's western border in its early days as a suburban strip, almost completely unrecognizable today.

Though not usually considered as such, early 20th century suburban developers were pioneers in adaptive reuse. With a few interior modifications, the the ample setbacks and lawns of former suburban residences were easily paved over to accomodate automobile-oriented commercial uses. Two such houses can be seen in the original view, converted into Tydol and Gulf Oil service stations.

Automobile-related businesses dominated western Lancaster Avenue from the very beginning of the 20th century. The Autocar Company set up shop in 1900 and remained Ardmore's largest employer through the early 1950s. Its factory buildings, destroyed by fire in 1956, are visible in the original photo. Though the Ardmore West strip mall replaced most of the Autocar site, the south side of the avenue remains crowded with car dealerships. Fascinatingly, the especially resilient Sunoco gas station at the corner of Lancaster and Woodside Avenues has been operating there since as early as 1926.

Sources:

1. "The First 300: The Amazing and Rich History of Lower Merion." Lowermerionhistory.org. 21 Nov. 2009. http://lowermerionhistory.org/texts/first300/index.html

2. Bromley, George W. and Walter S. Bromley. Atlas of Properties on Main Line Pennsylvania Railroad from Overbrook to Paoli. Atlas. Philadelphia: G.W. Bromley & Co, 1926.

Original image: "W Lancaster Avenue." 2008. Lower Merion/Narberth Buildings. Lowermerionhistory.org. Lower Merion Historical Society. 15 Nov. 2009. http://lowermerionhistory.org/buildings/image-building-list.php?building_id=407

Though not usually considered as such, early 20th century suburban developers were pioneers in adaptive reuse. With a few interior modifications, the the ample setbacks and lawns of former suburban residences were easily paved over to accomodate automobile-oriented commercial uses. Two such houses can be seen in the original view, converted into Tydol and Gulf Oil service stations.

Automobile-related businesses dominated western Lancaster Avenue from the very beginning of the 20th century. The Autocar Company set up shop in 1900 and remained Ardmore's largest employer through the early 1950s. Its factory buildings, destroyed by fire in 1956, are visible in the original photo. Though the Ardmore West strip mall replaced most of the Autocar site, the south side of the avenue remains crowded with car dealerships. Fascinatingly, the especially resilient Sunoco gas station at the corner of Lancaster and Woodside Avenues has been operating there since as early as 1926.

Sources:

1. "The First 300: The Amazing and Rich History of Lower Merion." Lowermerionhistory.org. 21 Nov. 2009. http://lowermerionhistory.org/texts/first300/index.html

2. Bromley, George W. and Walter S. Bromley. Atlas of Properties on Main Line Pennsylvania Railroad from Overbrook to Paoli. Atlas. Philadelphia: G.W. Bromley & Co, 1926.

Original image: "W Lancaster Avenue." 2008. Lower Merion/Narberth Buildings. Lowermerionhistory.org. Lower Merion Historical Society. 15 Nov. 2009. http://lowermerionhistory.org/buildings/image-building-list.php?building_id=407

Monday, November 16, 2009

Then and Now: Southwest corner of Lancaster and Cricket Avenues, Ardmore

Built sometime between 1913 and 1920, the nameless 3-story building at the corner of Cricket and Lancaster Avenues has long been one of Ardmore's most distinct buildings. It's a wonderfully detailed specimen of Renaissance Revival design, and given the high quality of craftsmanship evident in its construction, was almost certainly built for relatively wealthy inhabitants. Though merely an apartment building in function, it easily found itself among the town's most postcard-worthy sites during the 1920s.

What's particularly striking about the building's design is how resolutely urban it is. Though most buildings on Lancaster Avenue were built with upper-story apartment space, none of them are nearly as eager in their outward expression of a specific vision of residential life. Here, the abundant bay windows and balconies are strongly suggestive of density and old-school urbanity, out of step with dominant ideals about peaceful, reserved suburban living. It seems to reveal an original developer who had grander ambitions for Ardmore's future, at a time when growth had no foreseeable end.

Today, the building is one of historic Ardmore's greatest assets. Thankfully, despite modifications to its Lancaster Avenue storefronts, the original detailing of its upper stories remains remarkably intact. Unfortunately, two of its ground-floor retail spaces continue to underperform at the hands of a nail salon and spacious ATM cubicle. Needless to say, it really deserves better.

Source: Atlas of Properties on Main Line Pennsylvania Railroad From Overbrook to Paoli. Atlas. Philadelphia: A.H. Mueller, 1920.

Original image: "7 E Lancaster Ave." 2008. Lower Merion/Narberth Buildings. Lowermerionhistory.org. Lower Merion Historical Society. 15 Nov. 2009.

Monday, November 9, 2009

Then and Now: 13th and Sansom Streets looking southwest, Philadelphia

Few visitors to Philadelphia today, standing at the corner of 13th and Sansom, would feel much indication of 13th Street's turbulent recent history beneath its glimmering boutiques and restaurants. Neither, ufortunately, is any of it easily apparent in the above montage.

At the time of the original photo, 13th Street between Chestnut and Locust Streets was a fur district dotted with bars and luncheonettes serving office workers from South Broad Street. By the early 90s, 13th Street had become downtown's skid row and red light district, blamed upon the continuous western movement of Philadelphia's office district. Then, it attracted substantial attention from the press for its new reputation as Center City's most blighted street, a haven for prostitution, and the new center of gay nightlife. Officials decried it as an enormous black hole between the new Convention Center and the Avenue of the Arts theater district.

Remarkably, the area's turnaround is largely attributed to one individual, shrewd New York developer Tony Goldman. In 1998, Goldman Properties began purchasing buildings in the 13th Street area, investing millions into their renovation, and aggressively marketing the district to new retailers. No doubt, that story is overly simplistic, but the changes that have occurred in the decade since then have been nothing less than momentous. Today's 13th Street is one of downtown Philadelphia's liveliest retail corridors, and the proud heart of the city's gay community.

Source: Stoiber, Julie. "'The whole street is popping' - On 13th south of Chestnut, two blocks in a red-light district are turning funky." Philadelphia Inquirer. 3 Apr. 2006. Newsbank Access World News. Haverford College Library, Haverford, PA. 12 Nov. 2009.

Original photo: Carollo, R., and John McWhorter. "Historic Commission-3299-18." 1965. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 12 Nov. 2009.

Thursday, November 5, 2009

Then and Now: Southwest corner of 2nd and Laurel Streets, Philadelphia

After years of decay and abandonment, the southwest corner of 2nd and Laurel Streets, like many others in North Philadelphia, was reduced to a mere ghost of its former self. The corner building at 940 N. 2nd Street, once a produce market, now houses nothing more than a weed tree behind its sealed walls.

Thankfully, one has every reason to believe that better days are ahead. The 100 block of Laurel Street has been transformed thanks to phenomenal new developments by Onion Flats. Along 2nd Street, the corner is bookended by the Piazza at Schmidt's and Liberties Walk to the north and the thriving corner of 2nd and Poplar to the south.

Original photo: Mallis, Atheniasis T. "Public Works-41581-8." 1952. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 2 Nov. 2009.

Tuesday, October 27, 2009

New street furniture coming to Philadelphia

By the end of the year, the City of Philadelphia will put out its request for proposals (RFP) for a 20-year street furniture contract to replace its current one. Though the exact elements of the contract have yet to be decided, it will very likely include new bus shelters, bike racks, newsstand corrals, and information kiosks. This presents a major opportunity for Nutter's City Hall and Deputy Mayor Rina Cutler. Street furniture is an essential part of a city's appearance at street level, and the most successful cities understand the vital role that well-designed, distinctive street furniture can have in shaping the perceptions of visitors and residents alike.

By the end of the year, the City of Philadelphia will put out its request for proposals (RFP) for a 20-year street furniture contract to replace its current one. Though the exact elements of the contract have yet to be decided, it will very likely include new bus shelters, bike racks, newsstand corrals, and information kiosks. This presents a major opportunity for Nutter's City Hall and Deputy Mayor Rina Cutler. Street furniture is an essential part of a city's appearance at street level, and the most successful cities understand the vital role that well-designed, distinctive street furniture can have in shaping the perceptions of visitors and residents alike. The idea is generally well understood by European cities. Paris is perhaps the best example of a city that has reinforced the high quality of its public spaces through well-designed street furniture such as the bus shelter pictured above. Brussels' unique transit shelters pay homage to the city's Art Nouveau heritage. These two examples have been pictured above.

The idea is generally well understood by European cities. Paris is perhaps the best example of a city that has reinforced the high quality of its public spaces through well-designed street furniture such as the bus shelter pictured above. Brussels' unique transit shelters pay homage to the city's Art Nouveau heritage. These two examples have been pictured above. Meanwhile, Philadelphia has been stuck with some of the most underwhelming, nondescript street furniture of any major American city. Our current bus shelters are installed and maintained (just barely) by CBS Outdoor, an outdoor advertising firm which apparently has absolutely no appreciation for quality public design. Representative Richard Ament summed it up quite recently at the Academy of Natural Sciences when he explained, "We're not a design company." No kidding. For more examples of the junk that they offer, their site displays them quite proudly in a photo gallery (sort Media Type by Street Furniture).

Meanwhile, Philadelphia has been stuck with some of the most underwhelming, nondescript street furniture of any major American city. Our current bus shelters are installed and maintained (just barely) by CBS Outdoor, an outdoor advertising firm which apparently has absolutely no appreciation for quality public design. Representative Richard Ament summed it up quite recently at the Academy of Natural Sciences when he explained, "We're not a design company." No kidding. For more examples of the junk that they offer, their site displays them quite proudly in a photo gallery (sort Media Type by Street Furniture).Most fortunately, it looks like we will be able to do much better this time around. Also present at the Academy of Natural Sciences forum on Monday were representatives from Cemusa, JCDecaux and Clear Channel Adshel. Cemusa installed the very sleek bus shelters, automated toilets, and newspaper boxes that came to New York two years ago. Pioneering mega-firm JCDecaux operates Paris' street furniture, and claims to have invented the bus shelter. Likewise, Clear Channel Adshel has extensive experience in European cities. So there will be no lack of quality options. And best of all, since installation and capital costs are paid by the company, none of this will put a drain on the city's coffers. Let's just pray that they don't pick CBS Outdoor.

Lastly, the city is running a public opinion online survey. Please do tell City Hall what you think. This will shape the streets of Philadelphia for years to come.

Academy of Natural Sciences street furniture forum [PlanPhilly]

Monday, October 26, 2009

Then and Now: West side of 8th Street north of Bainbridge Street, Philadelphia

1969-2009

1969-2009Though most of South Philadelphia avoided the rampant destruction and abandonment that plagued other parts of the city, its historic building stock nonetheless suffered from its fair share of neglect and insensitive facade alterations. Built in the early 1880s, the Church of the Crucifixion has had its original Gothic Revival facade marred by the replacement of its arched windows with horizontal windows quite out of character with its design. Its neighbors on the northwest corner of 8th and Bainbridge Streets lost much of their elegance along with their storefronts.

Remnants of a bygone time, two of 8th Street's former trolley wire poles still stand at the intersection, currently serving as particularly tall signposts.

Source: Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

Original photo: "Historic Commission-12159-15." 1969. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 9 Sep. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=144357.

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

Then and Now: Southeast corner of 9th and Market Streets, Philadelphia

Perhaps no episode in the sad decline of Market East is as scarring as the disintegration of the Gimbel Brothers Department Store. Though not a home-grown institution like its many competitors (Strawbridge's, Wanamaker's, Lit Brothers, etc.) the store became a dominant landmark along Market Street. At its height, the Gimbels empire occupied the entire block of Market Street between 8th and 9th Streets, as well as a 12-story office and warehouse building on Chestnut Street. The building at the corner of 9th Street was designed by Addison Hutton in 1896 and originally built for Cooper & Conard, but quickly taken over by Gimbels. Its distinctive curved corner and arched facade are hauntingly memorable, adding to the surreal, ghostly quality of the original image.

In the 1970s, Gimbels became involved in plans for The Gallery at Market East as one of its main prospective tenants. Upon the completion of The Gallery I in 1977, Gimbels relocated its downtown flagship store to a plain concrete box at 10th and Market, abandoning its original complex one block to the east. Its former home was demolished shortly afterwards with the exception of its office tower at 833 Chestnut Street by Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White, though this is little consolation.

Barely a decade after the move, the Gimbels chain collapsed and its properties were sold. Its location in the Gallery is now occupied by a KMart store. The 800 block of Market Street, three decades after its demolition, remains an enormous vacant lot with little development prospect.

Sources:

1. Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

2. Fischer, John. "Gone but not forgotte - Gimbel's, Lit Brothers, Strawbridge & Clothier, and Wanamaker's Department Stores." About.com. 12 Oct. 2009. http://philadelphia.about.com/od/history/a/strawbridges.htm.

Original photo: "Department of City Transit-41118-0." Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 12 Oct. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=52491.

Thursday, October 8, 2009

Then and Now: 5 East Lancaster Avenue, Ardmore

Oddly enough, the squat stucco building at the corner of Lancaster and Anderson Avenues is in fact one of downtown Ardmore's oldest commercial buildings. The Merion Title & Trust Company built its first Ardmore office in 1897 before relocating in 1917 to a new classical revival edifice built adjacent to its former home. The original structure at the heart of town also housed a variety of tenants over the years, including a Post Office, library, and Western Union station. In 1977, all but the bottom two floors of the building were tragically destroyed in a fire, and were subsequently remodeled in a coat of stucco. Would it still merit preservation at this point? Perhaps the question will come up someday, if the logic of suburban development once again turns its eye to Ardmore's main street.

Source: Lower Merion Township: Searchable HR Database. Lower Merion Township Historical Commission. 30 Sep. 2009.

Original photo: "Ardmore Post Office Building." Lower Merion Historical Society Archives. Lowermerionhistory.org. Lower Merion Historical Society. 28 Sep. 2009.

http://www.lowermerion.org/Index.aspx?page=437

Source: Lower Merion Township: Searchable HR Database. Lower Merion Township Historical Commission. 30 Sep. 2009.

Original photo: "Ardmore Post Office Building." Lower Merion Historical Society Archives. Lowermerionhistory.org. Lower Merion Historical Society. 28 Sep. 2009.

http://www.lowermerion.org/Index.aspx?page=437

Tuesday, October 6, 2009

Then and Now: 16th and Sansom Streets looking west, Philadelphia

The 1600 block was not spared the gradual 20th century conversion of Sansom Street to a de facto service street dominated by parking garages and loading areas. This handsome commercial row on the 1601 block managed to survive until 2000, when it fell victim to one of the greatest crimes against historic preservation in Philadelphia's recent history, senselessly cleared to make way for a 12-story parking garage which never materialized. To make matters bitterly ironic, the developer, Wayne Spilove, was also serving as chairman of the Historical Commission at the time.

Original photo: "Department of City Transit-39825-0." 1969. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 2 Oct. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=52405

Friday, October 2, 2009

Then and Now: 16th and Sansom Streets looking east, Philadelphia

Hemmed in by towers and skyscrapers, the south side of the 1500 block of Sansom Street contains a row of narrow 2- and 3-story buildings housing a motley crew of small locally-owned shops, bars, and restaurants that feel far removed from their surrouding streets. By and large, these businesses would be unsuitable for the larger floor spaces or higher rents on Chestnut Street or Walnut Street, dominated for the most part by national and international retail chains. Sansom Street's shops add an invaluable contribution to the Rittenhouse area's retail mix and hence to its liveliness. It's Jane Jacobs' theory of diversity in action: a variety of building types and ages are a natural generator of activity.

Original photo: "Historic Commission-12827-37." 1969. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 21 Sep. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=152807

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

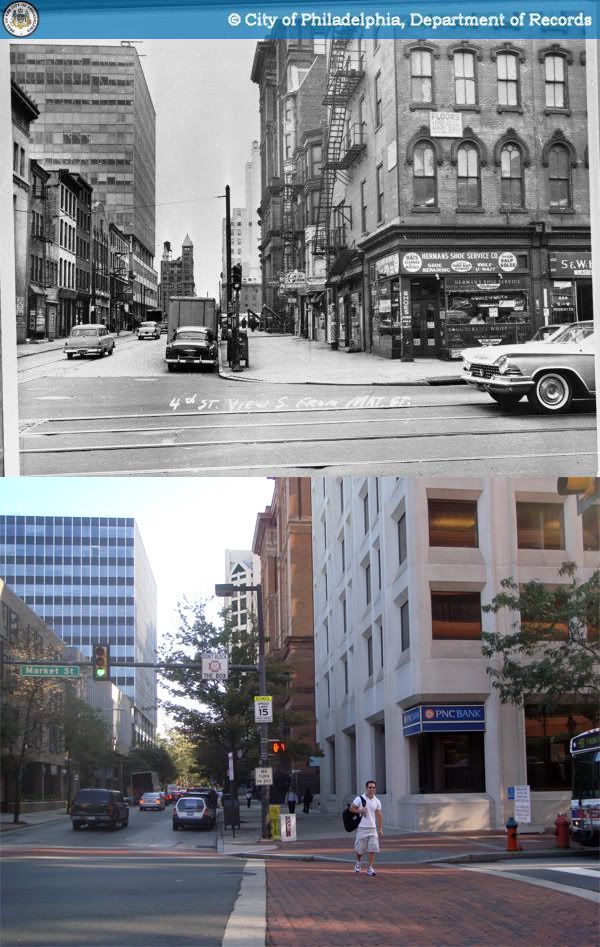

Then and Now: 4th and Market Streets looking south, Philadelphia

As the result of the gradual replacement of older buildings with poorly-designed new additions with minimal ground-floor retail presence, 4th Street suffers from an excess of blank walls and the typically moribund street life that plagues Old City's western edge. The boxy Continental Building (1970) on the southwest corner of 4th and Market is just about as bland as Modernism could ever get. I'm not sure when the WTXF/Fox 29 building was built across 4th street, yet its deadening effect upon the street wall is equally regrettable.

Original photo: "Department of City Transit-39516-0." 1959. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 2 Sep. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=33335.

Saturday, September 26, 2009

Jacques Gréber's 1917 Plan for Philadelphia

(enlarge for detail)

In 1917, with the Fairmount Parkway finally taking shape after years of planning, stalling, and demolition, the Fairmount Park Commission commissionned 34-year-old French architect and planner Jacques Gréber to prepare the final plans for the Parkway's layout and building siting. So it was likely with great confidence that he returned to Philadelphia from his Paris office later that year with his plans and sketches for the boulevard. Tucked among those was another plan, pictured here, showing a vision for all of central Philadelphia featuring a new set of radial avenues presumably of Gréber's invention.Having secured a commission as prestigious as the Parkway at a relatively young age, the ambitious Gréber likely fancied himself a bit as Philadelphia's 20th century Baron Haussmann. Somewhat unsurprisingly, his plan of axial streets linking a series of traffic circles, parks, and squares is quite reminiscent of the 1792 plan for Washington by Pierre Charles L'Enfant, the most renown French-American planner. I don't know how seriously Gréber expected his drawing to be received, and it certainly never gained much traction as an official planning document, yet it remains a particularly striking image to anyone with more than a passing knowledge of Philadelphia's street grid.

Interestingly, Gréber incorporated or extended the city's existing oblique streets into his network of new radial avenues. One of the more significant components of the plan was to extend Franklin Square two blocks to the west to meet Ridge Avenue at a new traffic circle à la Logan Circle to the west. "Franklin Circle" would also intersect with a new axis running from Reading Terminal at 11th and Market through Northern Liberties to a large park at Front and Germantown. Grays Ferry Avenue was extended to Rittenhouse Square, and Passyunk Avenue to a riverfront plaza at Front and Market.

Despite the many fanciful components of Gréber's vision like traffic circles at Broad and Fairmount and at 24th and Market, portions of it did curiously enough take shape under the auspices of future planners who had likely never seen this plan of his. Before becoming a sunken expressway, Vine Street was widened in the late 40s. The idea for a great plaza where Market Street meets the Delaware River would later be realized somewhat in the form of Penn's Landing. Gréber also pictured a reclaimed, park-like lower Schuylkill riverfront, which was at the time a mass of industrial buildings and rail yards around a tide of fetid waste. It was not until over 90 years later, after decades of wrangling and planning, that the Schuylkill Banks park as we know it began to take shape.

Image source: Gréber, Jacques. "Partial plan of the city shewing its new civic centre and the connexion of the Fairmount Parkway with the present street system & other proposed radial avenues." Drawing. Fairmount Park Art Association. The Fairmount Parkway. Philadelphia: Fairmount Park Art Association, 1919.

Sunday, September 20, 2009

Then and Now: Haverford Station

c. 1890-2009

Pictured here is the Pennsylvania Railroad's original station building at Haverford, named Haverford College Station until the 1890s. As with Wynnewood and Narberth, Haverford's station also served as the town's post office in its early days, which shows how instrumental the PRR was in the creation of Philadelphia's Main Line suburbs.

From former property atlases, it seems that Haverford Station Road originally crossed the tracks at-grade near the photo's vantage point. I'm guessing that the roadway was later dug under the tracks, and that a lower level addition was made to the building to accomodate the new elevation change, pictured below.

Today, Haverford station's ticket offices operate out of a newer building finished in 1916 on the opposite side of the tracks. The original station building is now leased to an antiques store on its lower level.

Today, Haverford station's ticket offices operate out of a newer building finished in 1916 on the opposite side of the tracks. The original station building is now leased to an antiques store on its lower level.Sources:

1. Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

2. G. Wm. Baist, Atlas of Properties along the Pennsylvania R.R. (Philadelphia, PA: J.L. Smith, 1887)

Images:

1. "Haverford Station (c.1890)." Lower Merion Historical Society Archives. Lowermerionhistory.org. Lower Merion Historical Society. 18 Sep. 2009. http://www.lowermerionhistory.org/photodb/web/html3/077-4.html

2. Lucius Kwok. "Haverford Station Pennsylvania." 2005. Wikipedia. 19 Sep. 2009. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Haverford_Station_Pennsylvania.jpg.

Monday, September 14, 2009

Quick Construction Update: Daskalakis Athletics Center

Drexel University's forthcoming addition to its Daskalakis Athletics Center is taking shape along the 3301 block of Market Street, and right now things are looking blue. In a weird way, the construction site feels like a temporary art installation; once the blue housewrap gets covered and the fencing goes down, the final product will have very little of its current color. The expansion will greatly improve Drexel's presence on Market Street, and could give the block a well-deserved new shot of life.

Drexel University's forthcoming addition to its Daskalakis Athletics Center is taking shape along the 3301 block of Market Street, and right now things are looking blue. In a weird way, the construction site feels like a temporary art installation; once the blue housewrap gets covered and the fencing goes down, the final product will have very little of its current color. The expansion will greatly improve Drexel's presence on Market Street, and could give the block a well-deserved new shot of life.

Saturday, September 12, 2009

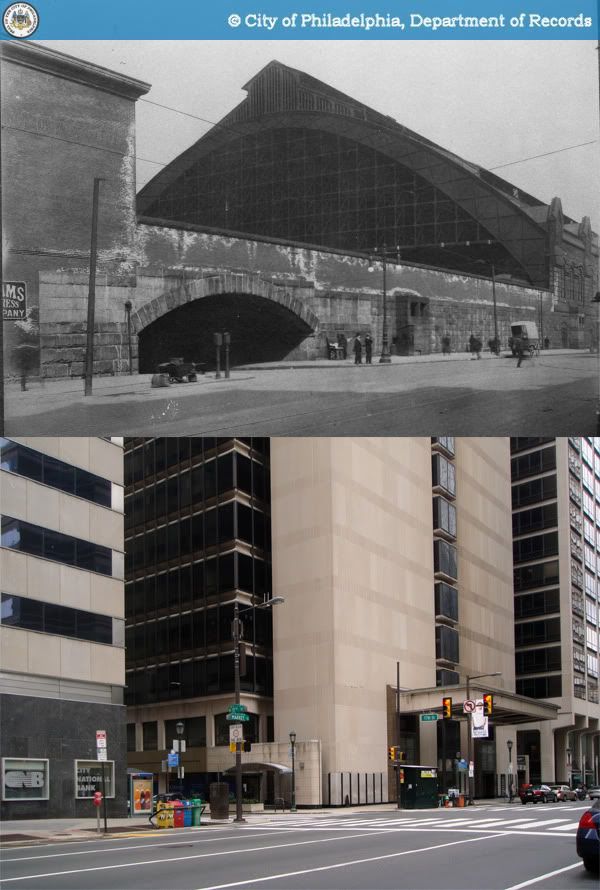

Then and Now: Northeast corner of 17th and Market Streets, Philadelphia

This is a street level view of what was formerly Broad Street Station's viaduct and massive train shed north of Market Street, now part of Penn Center. Though it definitely lacks activity outside of the workday, it remains a functional downtown district that seamlessly connects with its adjacent neighborhoods. In that respect, Philadelphia fared much better than many other cities which lost their train stations to decidedly very lackluster replacements.

For the most part, the Penn Center area is one massive showroom for the works of Vincent G. Kling & Associates. Though Kling never obtained the same international notoriety and acclaim as fellow Philadelphian architects Louis Kahn and Robert Venturi, no firm proved to be nearly as influential as his own in shaping Philadelphia's modern downtown thanks to a privileged relationship with the city's Planning Commission. Kling was behind Seven Penn Center, pictured in the center, Five Penn Center behind it, as well as the iconic Centre Square complex and the Municipal Services Building.

Original photo: "City Archives-828-0." 1912. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 7 Sep. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=55229

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

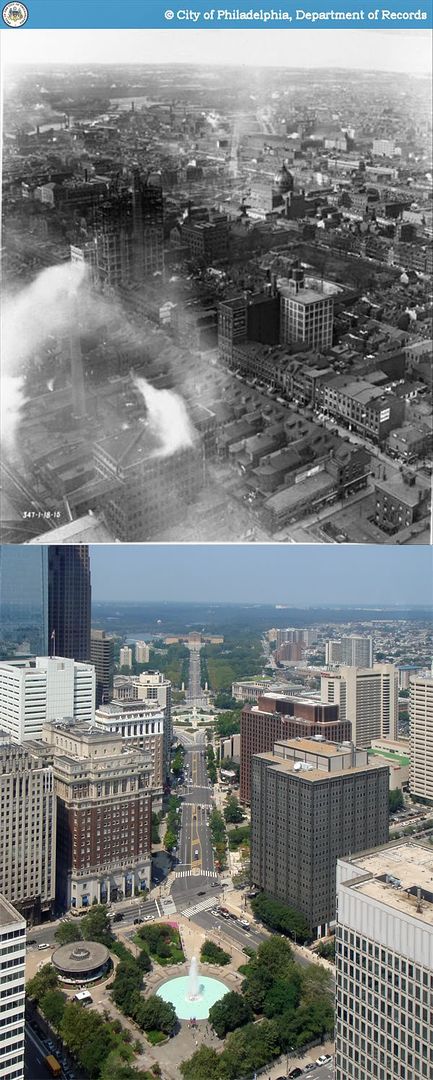

Then and Now: Northwest Center City viewed from City Hall tower, Philadelphia

In Philadelphia's collective memory, Broad Street Station seems to be best remembered not for the station building itself, but for its massive elevated viaduct which ran along toward Filbert Street toward the Schuylkill River, infamously known as the "Chinese Wall." Indeed, the railroad viaduct posed an enormous physical and economic barrier between Logan Square and the fashionable Rittenhouse Square area south of Market Street. Apart from the completion of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Northwest Center City saw relatively little development before 1950s.

After the Pennsylvania Railroad's rerouting of intercity trains to 30th Street Station and commuter rail lines to Suburban Station in the 1930s, Broad Street Station was made nearly obsolete, and its days were numbered. The demolition of the station and its accompanying tracks in 1953 opened a large swath of centrally located, high-value downtown land for redevelopment. In accordance with the city's plans, the corridor was to become a showpiece modern office district of the sort very in vogue among planners at the time. Over 60 years later, the Penn Center/Market West area remains downtown Philadelphia's premier office district.

The area has been so completely transformed that the only major building that survives from the original view is the John T. Windrim-designed Bell Telephone Building at 1613 Arch Street, seen under construction in the original photograph.

Original photo: Rolston, N.M. "Department of City Transit-969-0." 1915. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 6 Sep. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=18309.

Sunday, September 6, 2009

Then and Now: North Broad Street viewed from City Hall tower, Philadelphia

North Broad Street has always been home to an odd jumble of uses. By the early 20th century, the lower end near City Hall housed a small group of offices and institutional buildings, followed by concentration of large factories and warehouses between Vine and Spring Garden Streets. This general land use pattern remains hardly altered almost a century later, the largest single addition being the growth of Hahnemann University Hospital's campus.

North Broad's newest addition to come is the expansion of the Pennsylvania Convention Center, which will have 1 million square feet of saleable exhibition space upon completion, allowing the already massive building to maintain the distinction of having downtown Philadelphia's largest (and not green) roof.

It's a bit amusing to see the lines of cars parked in the median of Broad Street in the original photo, an odd Philadelphia tradition now confined to South Philadelphia.

A horizontally aligned comparison may be found here.

PCC expansion construction thread [Skyscraperpage]

Original Photo: Rolston, N.M. "Department of City Transit-950-0." 1915. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 31 Aug. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=18299.

Friday, September 4, 2009

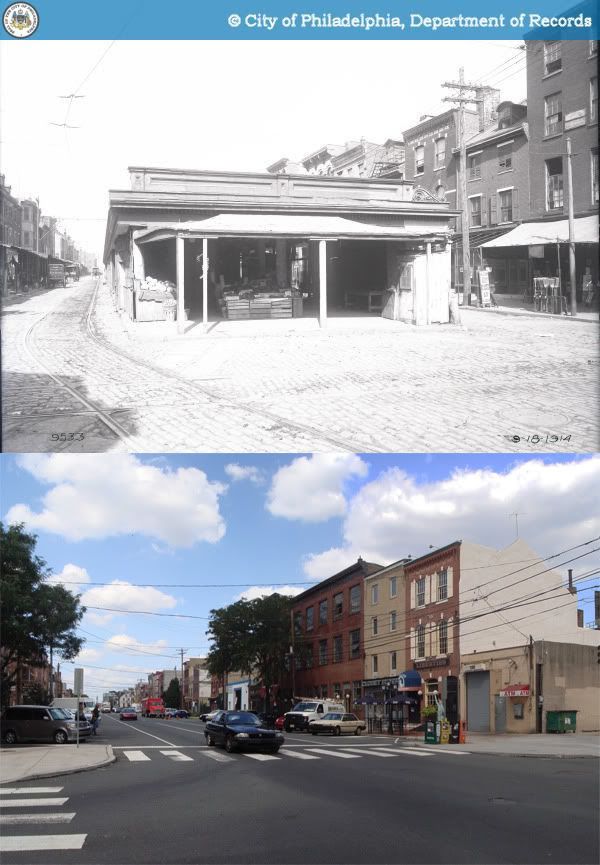

Then and Now: Looking north on 2nd Street from Fairmount Avenue, Philadelphia

1914-2009

Like many of Philadelphia's oldest neighborhoods, Northern Liberties had its own neighborhood market shed occupying the median of two blocks of N. 2nd Street between Fairmount Avenue and Poplar Street. The market stalls were demolished in the 1930s, coinciding with the general decline of neighborhood markets and the emergence of grocery stores and supermarkets. Headhouse Square in Society Hill is the last preserved example of Philadelphia's early street median markets, whose vestiges can also be found on Bainbridge Street and South 11th Street.

2nd Street is still Northern Liberties' main commercial strip, though the stretch where the market once stood doesn't quite match the vitality of parts of the street above and below it. At the moment, it's an odd mix of row homes and shops sprinkled with plenty of abandoned lots and light industrial buildings. The Northern Liberties Neighbors Association has identified the development of a more cohesive and vibrant 2nd Street as a major long-term goal and has studied several reconfigurations of the street in its 2005 Neighborhood Plan, as it seems to have a lot of potential that not currently being lived up to. I imagine that at some point they will begin to put more concrete plans into motion.

My own impulsive and not very developed vision would be for park space occupying the exact spot where the old market shed once stood, like a much smaller Boulevard Jules-Ferry in Paris, pictured above. 2nd Street is definitely wide enough here to support a small median park, it's really a question of political will and evaluating the exact economic benefits any such project would bring.

My own impulsive and not very developed vision would be for park space occupying the exact spot where the old market shed once stood, like a much smaller Boulevard Jules-Ferry in Paris, pictured above. 2nd Street is definitely wide enough here to support a small median park, it's really a question of political will and evaluating the exact economic benefits any such project would bring.Northern Liberties Neighborhood Plan [Northern Liberties Neighbors Association]

Market Interior photo: "Public Works-9534-0." 1914. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 2 Sep. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=10893.

Original photo: "Public Works-9539-0." 1914. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 2 Sep. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=16427.

Wednesday, September 2, 2009

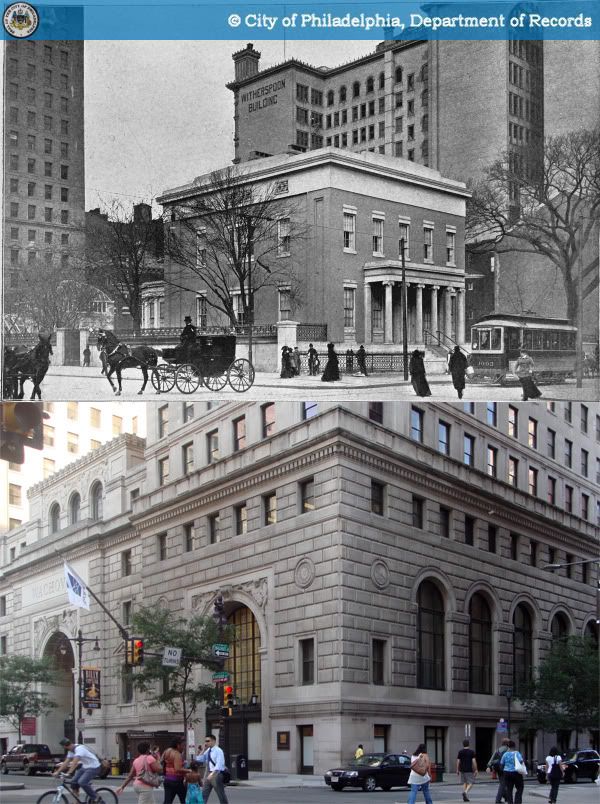

Then and Now: Northeast corner of Broad and Walnut Streets, Philadelphia

When the Dundas-Lippincott residence was built in 1839, Broad Street was still very much on the fashionable western periphery of Philadelphia, whose commercial activity was still clustered around Washington Square and present-day Old City. By 1900, the Dundas-Lippincott house was in its final days. The city's wealthy elite had firmly reestablished itself near Rittenhouse Square and the Dundas-Lippincott mansion and garden had become an odd anachronism amid a growing cluster of skyscrapers. This 1875 view from across Broad Street seems to be a good representation of the area's original appearance.

Since 1928, the site has been occupied by the Philadelphia Trust Company Building, today known as the Wachovia Building. Its architects, Simon & Simon, were behind several other of the city's minor landmarks of the time, including the Strawbridge & Clothier Building, Rodeph Shalom Synagogue, and parts of 69th Street Terminal in Upper Darby.

Since 1928, the site has been occupied by the Philadelphia Trust Company Building, today known as the Wachovia Building. Its architects, Simon & Simon, were behind several other of the city's minor landmarks of the time, including the Strawbridge & Clothier Building, Rodeph Shalom Synagogue, and parts of 69th Street Terminal in Upper Darby.

King's Views of Philadelphia [Places in Time]

Sources:

1. Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

2. "King's Views of Philadelphia." Places in Time. 1 Sep. 2009. http://www.brynmawr.edu/iconog/king/main5.html

Images:

1. Gutekunst, Frederick. " Dundas-Lippincott mansion, view from the northwest, showing grounds." Places in Time. 11 Mar. 2000. 1 Sep. 2009. http://www.brynmawr.edu/iconog/washw/development.html

2. "City Archives-976-0." 1903. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 31 Aug. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=59255

King's Views of Philadelphia [Places in Time]

Sources:

1. Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

2. "King's Views of Philadelphia." Places in Time. 1 Sep. 2009. http://www.brynmawr.edu/iconog/king/main5.html

Images:

1. Gutekunst, Frederick. " Dundas-Lippincott mansion, view from the northwest, showing grounds." Places in Time. 11 Mar. 2000. 1 Sep. 2009. http://www.brynmawr.edu/iconog/washw/development.html

2. "City Archives-976-0." 1903. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 31 Aug. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=59255

Sunday, August 30, 2009

Then and Now: Northwest corner of 37th and Spruce Streets, Philadelphia

1952-2009

1952-2009The original photograph seems to have been taken in anticipation of a period of major changes for West Philadelphia in the vicinity of the ever-expanding University of Pennsylvania. Soon after, Woodland Avenue's trolleys went underground into the expanded subway-surface tunnel. Woodland Avenue was closed to traffic east of 37th Street to become the University's Woodland Walk.

The shops on the northwest corner of 37th and Spruce made way for Vance Hall of the Wharton School, designed by Bower & Fradley and completed in 1972. Like many otherwise well-designed institutional buildings of the time, it projects an unfortunately cold presence to the sidewalk.

The shops on the northwest corner of 37th and Spruce made way for Vance Hall of the Wharton School, designed by Bower & Fradley and completed in 1972. Like many otherwise well-designed institutional buildings of the time, it projects an unfortunately cold presence to the sidewalk.

Original photo: Cuneo. "Department of City Transit-29597-0." 1952. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 23 Aug. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=50677

Thursday, August 27, 2009

Then and Now: Market East viewed from City Hall tower, Philadelphia

Though it seems much less gargantuan by today's standards, when John Wanamaker's Department Store (Now Macy's, bottom right corner) opened in 1910, it's grandeur and size were entirely in a league of their own. Designed by Chicago architect Daniel Burnham, at 15 stories and over 270 feet, Wanamaker's was by far the tallest building on Market Street east of City Hall, even dwarfing its closest competition, the Reading Terminal Headhouse.

The other true gem of Market East is of course the International Style masterpiece, the PSFS Building, completed in 1932 with the distinction of being the world's first true modernist skyscraper. It remains one of the finest examples of the International Style in North America.

A horizontally aligned comparison may be found here.

Photographs of the PSFS Building [PhillySkyline]

Source: "Wanamaker Building, Philadelphia." Emporis.com. 27 Aug. 2009. http://www.emporis.com/application/?nav=building&lng=3&id=wanamakerbuilding-philadelphia-pa-usa

Original photo: Rolston, N.M., "Department of City Transit-954-0." 1915. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 27 Aug. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=18303

Monday, August 24, 2009

Then and Now: South Broad Street viewed from City Hall tower, Philadelphia

At the turn of the 20th century, Broad Street south of City Hall had become Philadelphia's new center of business and finance, and home to the city's first cluster of skyscrapers, long before subsequent growth along Walnut Street west of Broad or the explosive development of Market West and Penn Center. The stretch received several major additions in the 20s and 30s, the most visible including the PNB Building, the Girard Trust Company across the street (now Ritz-Carlton Hotel), and the Fidelity-Philadelphia Trust Company Building (now Wachovia). Having seen few large developments since WWII, to this day South Broad Street retains its classic early 20th-century character.

A horizontally aligned comparison shot can also be found here.

Source: Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

Original photo: Rolston, N.M. "Department of City Transit-957-0." 1915. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 24 Aug. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=18305

Friday, August 21, 2009

Then and Now: Northeast Center City viewed from City Hall tower, Philadelphia

I'm think the original photographer, a certain N.M. Rolston, would be more than a bit puzzled were he around today to look over Reading Terminal, only to see no railroad viaduct leading out of the trainshed, but a skybridge connecting to an enormously wide (and still growing) Pennsylvania Convention Center exhibition hall. The trains still run today, just underground in the Center City Commuter Tunnel. Much of the seedy landscape of factories, flophouses, and taverns that once dotted this part of downtown disappeared amid new hotels, office towers, and garages. The only area that has conserved much of its old appearance is present-day Chinatown, just east of the Convention Center.

A horizontally aligned comparison shot can also be found here

Original photo: Rolston, N.M. "Department of City Transit-953-0." 1915. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 18 Aug. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=18301

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

Construction update: JFK Boulevard Bridge, Philadelphia

While the South Street Bridge's redesign has received a good deal of press recently, PennDOT has finally finished its resurfacing and rehabilitation project the John F. Kennedy Boulevard Bridge after over two years of closures.

While the South Street Bridge's redesign has received a good deal of press recently, PennDOT has finally finished its resurfacing and rehabilitation project the John F. Kennedy Boulevard Bridge after over two years of closures.I'm happy to say that it's a solid improvement over the regular old highway bridge it once was. The new pedestrian-scaled lights on the bridge itself are well-placed between the sidewalk and roadway, making the bridge much more pleasant to walk across. The distinctive sidewalk paving and new benches are also very welcome additions - PennDOT and the City deserve a round of applause on this one. Really, improvements like these really couldn't come soon enough for the Chestnut and Walnut St. Bridges and the rest of the 30th Street Station area.

Tuesday, August 18, 2009

Then and Now: The Parkway viewed from City Hall tower, Philadelphia

One of the true gems to be found on PhillyHistory.org is a small series of photos taken in 1915 from City Hall tower's observation deck. Roughly 500 feet above ground, it remains the city's tallest observation area open to the public, and its location at the heart of Center City lends it the most magnificent view of central Philadelphia.

Although the city has changed significantly in every direction, no view is as radically different as the perspective towards what is now the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. In 1915, the Parkway was barely in its infancy; demolition for the new right-of-way had begun on the site of the former Fairmount Reservoir, and was making its way toward City Hall. The original photograph gives a powerful sense of the sheer enormity of the project, of planners and civic leaders who dreamed of nothing less than the complete reshaping of the American city. This great ambition was on a scale truly befitting a rapidly emerging, daring, and somewhat brash new nation. Indeed, wholesale demolition and reconstruction of existing urban areas these days seems to be the sole province of places like China and Dubai.

The old photograph also provides a quick glimpse of a Logan Square neighborhood which we would not recognize today, one with a rich mix of row houses, factories, and warehouses. Most of that was quickly redeveloped after the creation of the Parkway and the later replacement of Broad Street Station and its railway viaduct in the 50s.

A horizontally aligned comparison shot can also be found here.

Original photo: "Department of City Transit-347-0." 1915. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 17 Aug. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=56023

Saturday, August 15, 2009

Then and Now: 11th and Market Streets looking west, Philadelphia

Nothing quite looks the same on the 1100 block of Market Street. Snellenburg's is gone, The Gallery II is now across the street, and the streetscape has gotten new lights, paving, planters, trees, newspaper boxes and stands, trash cans, bus shelters, and even a reconfigured subway stop. It's a nice surprise then to see the streetcar pole for the former Route 23 trolley standing right where it's always been.

Original photo: Balionis, Francis. "Public Works-41807-6." 1952. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 8 Aug. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=33365

Tuesday, August 11, 2009

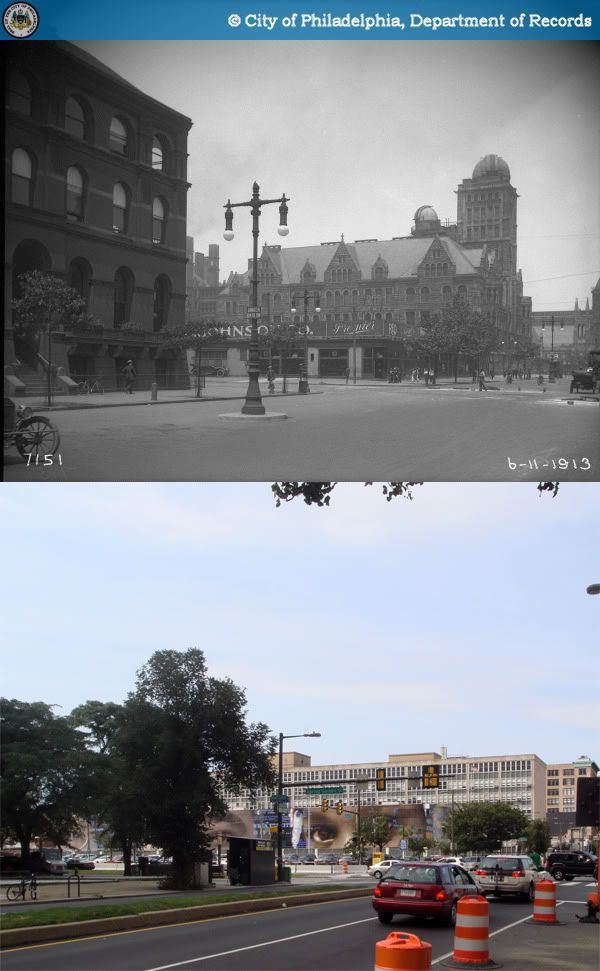

Then and Now: Broad and Spring Garden Streets looking North, Philadelphia

1913-2009

1913-2009The southwest corner of Broad and Spring Garden (photo left) had become a gas station by the early 40s, before being replaced in 1958 by the State Office Building and plaza. Central High School on the center right (which will hopefully have its own post soon) was succeeded by the decidedly less inspiring Benjamin Franklin High School, also completed in 1958.

Sources:

1. Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

2. "Philadelphia Land Use Map, 1942." Library Company of Philadelphia. Philadelphia Geohistory Network. Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

Original Photo: "Public Works-7151-0." 1913. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 6 Aug. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=19917

Sources:

1. Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

2. "Philadelphia Land Use Map, 1942." Library Company of Philadelphia. Philadelphia Geohistory Network. Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

Original Photo: "Public Works-7151-0." 1913. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 6 Aug. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=19917

Sunday, August 9, 2009

Everything wrong with Independence Mall, Philadelphia

What the folks at the Independence Visitors' Center won't tell you is that the heart of Philadelphia's "most historic square mile" is ironically also the worst preserved section of the city's downtown. Shortly after the National Park Service's creation of Independence National Historic Park around Old City and Independence Hall in 1948 (which involved its own destruction of old but not "historic" buildings) Philadelphia megaplanner Ed Bacon and associated Planning Commission began to devise what would be their worst plan ever implemented.

Very much a modern apparition of City Beautiful planning, the vision of Independence Mall was to create a new axis north of Independence Hall by widening 5th and 6th Streets between Chestnut and Race Streets, replacing everything in between 5th and 6th with parkland, and lining it all with new corporate and civic buildings of uniform massing. There was apparently no perceived shame or contradiction in demolishing several fine-grained, 19th century, uniquely Philadelphian downtown blocks to extend a historic park ("it ain't historic unless it's red brick colonial!")

Very much a modern apparition of City Beautiful planning, the vision of Independence Mall was to create a new axis north of Independence Hall by widening 5th and 6th Streets between Chestnut and Race Streets, replacing everything in between 5th and 6th with parkland, and lining it all with new corporate and civic buildings of uniform massing. There was apparently no perceived shame or contradiction in demolishing several fine-grained, 19th century, uniquely Philadelphian downtown blocks to extend a historic park ("it ain't historic unless it's red brick colonial!")

Even more depressing is how incredibly lackluster its replacement is. To begin with, the immense scale of the Mall acts as a significant barrier to pedestrian connectivity between Market East and Old City. Save for the Rohm & Haas headquarters, 5th and 6th Streets along the Mall are home to the city's most uninspiring Modernist architecture, with absolutely atrocious sidewalk presence. The terrible urban design here creates an incredible deadening effect on a three-block stretch between 4th and 7th Streets, decimating any form of street life. Very much a modern apparition of City Beautiful planning, the vision of Independence Mall was to create a new axis north of Independence Hall by widening 5th and 6th Streets between Chestnut and Race Streets, replacing everything in between 5th and 6th with parkland, and lining it all with new corporate and civic buildings of uniform massing. There was apparently no perceived shame or contradiction in demolishing several fine-grained, 19th century, uniquely Philadelphian downtown blocks to extend a historic park ("it ain't historic unless it's red brick colonial!")

Very much a modern apparition of City Beautiful planning, the vision of Independence Mall was to create a new axis north of Independence Hall by widening 5th and 6th Streets between Chestnut and Race Streets, replacing everything in between 5th and 6th with parkland, and lining it all with new corporate and civic buildings of uniform massing. There was apparently no perceived shame or contradiction in demolishing several fine-grained, 19th century, uniquely Philadelphian downtown blocks to extend a historic park ("it ain't historic unless it's red brick colonial!")The Mall never generated the kind of visitor traffic used by planners to justify the project, and the National Park Service recently finished a complete re-landscaping of the Mall's open space in an effort to increase visitation. Neither is it much of an amenity to local residents, as there is nary a Philadelphian who volunteers to spend his or her free time here. None of this is really unexpected if one believes that parks are only as vibrant as their immediate surroundings.

It's simply a travesty that Independence Mall, the city's premier tourist site just steps away from the symbolic birthplace of American democracy, is such a terribly boring place with no visible history to speak of. Yes, these are harsh words, but I'm certain that these thoughts will ring true to many others.

It's simply a travesty that Independence Mall, the city's premier tourist site just steps away from the symbolic birthplace of American democracy, is such a terribly boring place with no visible history to speak of. Yes, these are harsh words, but I'm certain that these thoughts will ring true to many others.The famous Chicago planner Daniel Burnham is often remembered for the statement, "Make no small plans; they have no magic to stir men's blood." But we would do just as well to keep in mind that big plans can easily become big mistakes.

Photo credit:

1. Gehr, Herbert. "Independence Hall Philadelphia." LIFE Photo Archive. Google Images. 9 Aug. 2009. http://www.gstatic.com/hostedimg/3a8466011e8effa8_large

2. Independence National Historic Park. "Independence Mall, 1979." Greater Philadelphia Tourism Marketing Corporation. Gophila.com. 9 Aug. 2009. http://press.gophila.com/media/1112

Friday, August 7, 2009

Then and Now: Philadelphia main post office, 30th and Market Street, Philadelphia

Alongside 30th Street Station just across Market Street, Philadelphia's former main post office is one of the city's most imposing civic buildings. Its architects, Rankin & Kellogg, were also responsible for many of the city's most iconic early 20th century buildings, including the Architects' Building, the Inquirer Building. and the Provident Trust Company tower. The structure was also a substantial engineering feat, built on a platform above 30th Street Station's railroad tracks in 1935.

Unfortunately, I never had the pleasure of seeing its grand interior before the post office closed several years ago, and presumably never will. The building is currently being renovated for the Internal Revenue Service's new Philadelphia office, as part of the University of Pennsylvania and Brandywine Realty Trust's Cira Centre South project. The former 30th Street loading docks slightly visible in the photo are set to be converted to an outdoor terrace for IRS workers. The Bolt Buses will probably have to load somewhere else once that happens.

Cira Centre South [Skyscraperpage]

Original photo: Wenzell J. Hess, "Public Works-41057-0-C." 1950. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=68115

Wednesday, August 5, 2009

Then and Now: 2138 Market Street, Philadelphia

Though the Salvation Army does lots of good, charitable deeds, I can't quite say as much about their building preservation savvy. It's sad to see perfectly good tall shop windows go to waste under an ugly layer of stucco, not to mention the awful aluminum mansard roof imitation.

Original photo: Cuneo. "Department of City Transit-29897-0." 1953. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 3 Aug. 2009. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=51097

Monday, August 3, 2009

What's in a bus stop?

Here in Philadelphia, SEPTA runs a very extensive bus network that (at least on weekdays) provides good and frequent service on most city routes. This is probably one of the city's most well-guarded secrets. For just about anyone who's never needed to get somewhere by bus, the whole thing's an enormous, inscrutable mystery. In many ways, it comes down to a simple problem of signage.

SEPTA's bus stops aren't actually invisible, but to transit newbies, they might as well be. The vast majority of their stops are marked by small signs attached to light or power poles, easily lost among other messy streetscape elements. But that's really the least of our problems. The signs themselves provide minimal descriptions of route endpoints and major roads taken, but even if one is familiar enough with the city's geography to know where those are, most routes tend to wind around quite a bit, so it's really not saying very much. There's a customer service number you could call, or you could wait for the bus and ask the driver, but who really wants to bother with that?

Of course it doesn't need to be this way. There are lots of transit agencies out there that have their bus stops very well thought out, perhaps none more so than Paris. Each stop with a bus shelter (most of them) is equipped with route maps, system maps, a neighborhood map, and a nifty electronic screen that displays waiting times for each route.

Of course it doesn't need to be this way. There are lots of transit agencies out there that have their bus stops very well thought out, perhaps none more so than Paris. Each stop with a bus shelter (most of them) is equipped with route maps, system maps, a neighborhood map, and a nifty electronic screen that displays waiting times for each route.

Unfortunately, this costs a lot of money, something which SEPTA and most US transit agencies have historically been short on. But an effective and informative system can still be devised on a more restricted budget. For an indication of how much information can be packed into small signs, Taipei provides a sharp example. Each bus signpost has a basic map listing all stops, transfers to rail services, off-peak and peak hour frequencies, and first and last bus times.

Unfortunately, this costs a lot of money, something which SEPTA and most US transit agencies have historically been short on. But an effective and informative system can still be devised on a more restricted budget. For an indication of how much information can be packed into small signs, Taipei provides a sharp example. Each bus signpost has a basic map listing all stops, transfers to rail services, off-peak and peak hour frequencies, and first and last bus times.

It's already miles ahead of what SEPTA provides - to get any of that kind of information most of us just have to spend our time fumbling through route maps online or in stations. Attracting more people to transit is one of the most important challenges of the 21st century, and all forms of transit should be made as easily navigable as possible to draw new ridership. The biggest hurdle in learning a bus system is finding bus stops, routes, and where they connect. Unfortunately, SEPTA makes this about as hard as it could be. Putting aside notions of social stigma that surrounds taking the bus, is it any wonder that buses have few casual riders given how inaccessible the system is? If SEPTA really wants to be a world class transit network the city deserves, this isn't going to cut it anymore.

It's already miles ahead of what SEPTA provides - to get any of that kind of information most of us just have to spend our time fumbling through route maps online or in stations. Attracting more people to transit is one of the most important challenges of the 21st century, and all forms of transit should be made as easily navigable as possible to draw new ridership. The biggest hurdle in learning a bus system is finding bus stops, routes, and where they connect. Unfortunately, SEPTA makes this about as hard as it could be. Putting aside notions of social stigma that surrounds taking the bus, is it any wonder that buses have few casual riders given how inaccessible the system is? If SEPTA really wants to be a world class transit network the city deserves, this isn't going to cut it anymore.

SEPTA's bus stops aren't actually invisible, but to transit newbies, they might as well be. The vast majority of their stops are marked by small signs attached to light or power poles, easily lost among other messy streetscape elements. But that's really the least of our problems. The signs themselves provide minimal descriptions of route endpoints and major roads taken, but even if one is familiar enough with the city's geography to know where those are, most routes tend to wind around quite a bit, so it's really not saying very much. There's a customer service number you could call, or you could wait for the bus and ask the driver, but who really wants to bother with that?

Of course it doesn't need to be this way. There are lots of transit agencies out there that have their bus stops very well thought out, perhaps none more so than Paris. Each stop with a bus shelter (most of them) is equipped with route maps, system maps, a neighborhood map, and a nifty electronic screen that displays waiting times for each route.

Of course it doesn't need to be this way. There are lots of transit agencies out there that have their bus stops very well thought out, perhaps none more so than Paris. Each stop with a bus shelter (most of them) is equipped with route maps, system maps, a neighborhood map, and a nifty electronic screen that displays waiting times for each route.

Unfortunately, this costs a lot of money, something which SEPTA and most US transit agencies have historically been short on. But an effective and informative system can still be devised on a more restricted budget. For an indication of how much information can be packed into small signs, Taipei provides a sharp example. Each bus signpost has a basic map listing all stops, transfers to rail services, off-peak and peak hour frequencies, and first and last bus times.

Unfortunately, this costs a lot of money, something which SEPTA and most US transit agencies have historically been short on. But an effective and informative system can still be devised on a more restricted budget. For an indication of how much information can be packed into small signs, Taipei provides a sharp example. Each bus signpost has a basic map listing all stops, transfers to rail services, off-peak and peak hour frequencies, and first and last bus times. It's already miles ahead of what SEPTA provides - to get any of that kind of information most of us just have to spend our time fumbling through route maps online or in stations. Attracting more people to transit is one of the most important challenges of the 21st century, and all forms of transit should be made as easily navigable as possible to draw new ridership. The biggest hurdle in learning a bus system is finding bus stops, routes, and where they connect. Unfortunately, SEPTA makes this about as hard as it could be. Putting aside notions of social stigma that surrounds taking the bus, is it any wonder that buses have few casual riders given how inaccessible the system is? If SEPTA really wants to be a world class transit network the city deserves, this isn't going to cut it anymore.

It's already miles ahead of what SEPTA provides - to get any of that kind of information most of us just have to spend our time fumbling through route maps online or in stations. Attracting more people to transit is one of the most important challenges of the 21st century, and all forms of transit should be made as easily navigable as possible to draw new ridership. The biggest hurdle in learning a bus system is finding bus stops, routes, and where they connect. Unfortunately, SEPTA makes this about as hard as it could be. Putting aside notions of social stigma that surrounds taking the bus, is it any wonder that buses have few casual riders given how inaccessible the system is? If SEPTA really wants to be a world class transit network the city deserves, this isn't going to cut it anymore.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)