Saturday, September 4, 2010

I've moved

It's taken a while, but I've finally gotten settled in Los Angeles. For those who would be interested, I have also decided to continue writing from a new blog called Urban Diachrony. For for the time being, it will be a little more photoblog-like, and a lot lighter on written content until I get myself a bit more oriented here. Happy Labor Day weekend!

Original photo: Butterfield, Chalmers. "Brown Derby Restaurant, Los Angeles, Kodachrome." Wikimedia Commons. Wikipedia. 20 Aug. 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Brown_Derby_Restaurant_,_Los_Angeles_,_Kodachrome_by_Chalmers_Butterfield.jpg.

Monday, August 2, 2010

Then and Now: Ximen Circle, part 2

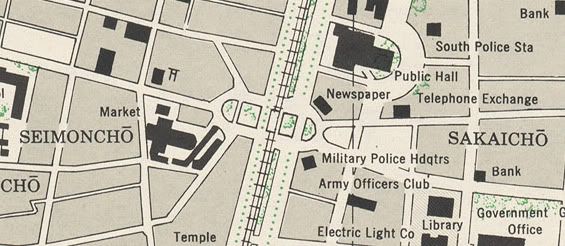

Ximen Circle is a particularly fascinating place in Taipei's history in no small part because it was arguably the city's most fantastically complicated and chaotic intersection. Up until the end of the 20th century, streets branched out in seven directions, and furthermore, the entire traffic circle was bisected by a busy at-grade railroad crossing. Meanwhile, pedestrian circulation was facilitated by several elevated pedestrian walkways. Visible in the right foreground of the original photo above is a portion of Zhonghua Market (中華商場), an eight-block market complex that occupied the center of Zhonghua Road (中華路), alongside the railroad tracks.

The intersection's configuration dates back to the early days of Japanese colonization. After the Japanese empire took control of Taiwan in 1895, it took few delays in shaping Taipei into the island's provincial capital. In 1900, the colonial government began to dismantle its city walls, replacing them with a series of boulevards, including Zhonghua Road on the western side. The walled city's western gate was demolished and replaced by an elliptical plaza and traffic circle, shaped like a smaller version of the Place de la République in Paris. Railroad tracks were built in the median of Zhonghua Road shortly afterward.

That design remained essentially unchanged up through the 1980s, when the city embarked on several ambitious efforts to modernize its infrastructure. Underground railroad tunnels were built to replace all at-grade tracks west of Taipei Main Station; the Zhonghua Road rails were removed when the tunnels opened in 1989. Demolition of the struggling Zhonghua Market complex began in the following year. Later in the 1990s, Ximen Circle was rebuilt as a four-way intersection during construction of the Taipei Metro's first east-west subway route, now the Nangang Line. Both projects were completed in 1999.

1972-2010

1972-2010

Then and Now photographs:

1. Carpenter, N. "Oversea Chinese Emporium Ltd." 1970. Shulinkou Air Station. 24 Jul. 2010. http://members.tripod.com/Shulinkou/shimading2.jpg.

2. Duffin, L. "1972 shot of the same location and view as photo #1 above." 1972. Shulinkou Air Station. 24 Jul. 2010. http://members.tripod.com/Shulinkou/tpe019a.jpg.

Other photographs:

1. "0005017388 - 台北市西門町." 1978. 行政院新聞局. 國家文化資料庫. 行政院文化建設委員會. 2 Aug. 2010. http://nrch.cca.gov.tw/metadataserverDevp/DOFiles/jpg/00/05/12/33/cca100069-hp-0006640030-0001-i.jpg.

2. U.S. Army Map Service. "Taihoku-Matsuyama." 1945. Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection. University of Texas Libraries. 2 Aug. 2010. http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/ams/formosa_city_plans/txu-oclc-6565483.jpg.

The intersection's configuration dates back to the early days of Japanese colonization. After the Japanese empire took control of Taiwan in 1895, it took few delays in shaping Taipei into the island's provincial capital. In 1900, the colonial government began to dismantle its city walls, replacing them with a series of boulevards, including Zhonghua Road on the western side. The walled city's western gate was demolished and replaced by an elliptical plaza and traffic circle, shaped like a smaller version of the Place de la République in Paris. Railroad tracks were built in the median of Zhonghua Road shortly afterward.

That design remained essentially unchanged up through the 1980s, when the city embarked on several ambitious efforts to modernize its infrastructure. Underground railroad tunnels were built to replace all at-grade tracks west of Taipei Main Station; the Zhonghua Road rails were removed when the tunnels opened in 1989. Demolition of the struggling Zhonghua Market complex began in the following year. Later in the 1990s, Ximen Circle was rebuilt as a four-way intersection during construction of the Taipei Metro's first east-west subway route, now the Nangang Line. Both projects were completed in 1999.

1972-2010

1972-2010Then and Now photographs:

1. Carpenter, N. "Oversea Chinese Emporium Ltd." 1970. Shulinkou Air Station. 24 Jul. 2010. http://members.tripod.com/Shulinkou/shimading2.jpg.

2. Duffin, L. "1972 shot of the same location and view as photo #1 above." 1972. Shulinkou Air Station. 24 Jul. 2010. http://members.tripod.com/Shulinkou/tpe019a.jpg.

Other photographs:

1. "0005017388 - 台北市西門町." 1978. 行政院新聞局. 國家文化資料庫. 行政院文化建設委員會. 2 Aug. 2010. http://nrch.cca.gov.tw/metadataserverDevp/DOFiles/jpg/00/05/12/33/cca100069-hp-0006640030-0001-i.jpg.

2. U.S. Army Map Service. "Taihoku-Matsuyama." 1945. Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection. University of Texas Libraries. 2 Aug. 2010. http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/ams/formosa_city_plans/txu-oclc-6565483.jpg.

Saturday, July 24, 2010

Then and Now: Ximen Circle (西門圓環), Taipei

Since the end of World War II, Taipei's Ximending district (西門町) has been one of the city's largest retail and entertainment hubs, as well as a major center of local youth culture. The neighborhood is one of few places in Taiwan to have retained its Japanese colonial period name, literally "west gate town," owing to its location immediately outside of Taipei's western walls. Though the city walls were dismantled in 1905, Ximending's main entrance continues to face the major intersection that has replaced the western gate, long known as Ximen Circle.

The intersection underwent an enormous reconfiguration during the 1990s, which included the conversion of the traffic circle into a single, essentially four-way crossing, replacing the central plaza with smaller ones along the edges, one of which is shown above. The Ximen Taipei Metro station opened in 1999, and has consistently been one of the most heavily used stops in the system.

Original photo: Carpenter, N. "Looking back at the traffic circle in the opposite direction." 1970. Shulinkou Air Station. 23 Jul. 2010. http://members.tripod.com/Shulinkou/shimading5.jpg.

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

Then and Now: Intersection of Zhongshan and Minquan Roads looking south, Taipei

The Zhongshan and Minquan Road intersection is still busy today, although it's no longer one of downtown Taipei's most important crossroads. Most of Taipei's major avenues were reconfigured and landscaped in the 1950s and 60s; the trees running down Zhongshan Road's two median strips in the original photo appear to have been planted only several years earlier.

The hotel building in the background with the circular rooftop restaurant, known as the Center Hotel in 1970, was later reopened as the Fortuna Hotel (富都大飯店), which closed in 2007 and was demolished shortly afterwards. The four two-story commercial buildings just off of the street corner on the right side still remain, although somewhat hidden underneath a billboard addition.

Original photo: Lentz, R. "Central Hotel and Back Street Market" 1970. Shulinkou Air Station. 19 Jul. 2010. http://shulinkou.tripod.com/rlcentralhtl70.jpg.

Tuesday, July 13, 2010

Then and Now: FuShun St, Taipei

In the 1960s and 70s, the side streets off of Zhongshan North Road, Section 2 housed a number of bars and nightclubs that were mainly popular among American servicemen and other expats. Pictured here is FuShun Street (撫順街), once home to a number of such establishments like the Queen's Club, the Hawaii Bar, and the Arcade Bar.

40 years later, the American military presence in Taiwan is long gone, and the neighborhood is no longer much of a nightlife hotspot. Today's FuShun Street, substantially more built up, is a rather typical-looking side street, and almost completely unrecognizable from its former appearance. However, one building seems to remain from the original view: the bunker-like concrete building in the right foreground.

Original photo: Carpenter, N. "Looking down Fu-Shun Street." 1970. Shulinkou Air Station. 13 Jul. 2010. http://shulinkou.tripod.com/queens2.jpg

Sunday, July 11, 2010

1970s Taipei through American eyes

It's not the most obvious place one would expect to find a bunch of old photographs of Taipei, but a website (on Tripod, no less) maintained by former U.S. military personnel stationed at Shulinkou Air Station happens to have a small but valuable collection of such photos. The 6987th Security Group was one of many American military units stationed in Taiwan between 1955 and 1977, during the period of formal military cooperation between the United States military and the Republic of China government. The website is a messy one to navigate, but it offers a few fascinating glimpses of expatriate life in the island's capital city.

It's not the most obvious place one would expect to find a bunch of old photographs of Taipei, but a website (on Tripod, no less) maintained by former U.S. military personnel stationed at Shulinkou Air Station happens to have a small but valuable collection of such photos. The 6987th Security Group was one of many American military units stationed in Taiwan between 1955 and 1977, during the period of formal military cooperation between the United States military and the Republic of China government. The website is a messy one to navigate, but it offers a few fascinating glimpses of expatriate life in the island's capital city.Their photographs reveal a city that was in many ways dramatically different from contemporary Taipei, and one which doesn't usually invite much nostalgia. In the 1970s, it was by all accounts a rather drab, gritty place, with little of the cosmopolitan glamour of other East Asian metropolises like Hong Kong or Tokyo. Despite rapid population growth, the central city remained relatively low-slung, with extremely few high-rise buildings. The city's downtown remained largely concentrated along Zhongshan Road, and had yet to be be overtaken by fast-growing districts to the east.

Unfortunately, many of the vantage points that these photographs were taken from no longer exist or are no longer publicly accessible, a principle cause being the destruction of the elevated pedestrian walkways that once crossed over most of the city's major intersections. Again, it's not an easy website to get around, but for anyone acquainted with contemporary Taipei, it's worth a look.

Photo credits:

1. Carpenter, M. "Making the rounds in Taipei." 1970. Shulinkou Air Station. 11 Jul. 2010. http://members.tripod.com/Shulinkou/dawgx3b.jpg.

2. Swallom, S. "The intersection of Min Chuan East Road and Hsin Shen North Road." 1970. Shulinkou Air Station. 11 Jul. 2010. http://shulinkou.tripod.com/pbminchuanrd2.jpg.

3. Duffin, L. "1972 shot of Chung-Hua Road." 1972. Shulinkou Air Station. 11 Jul. 2010. http://shulinkou.tripod.com/ldshim7178.jpg.

Monday, July 5, 2010

Brian goes to Los Angeles

I'm afraid that I have some unfortunate news for my Philadelphia area readers. Looking back now, my first post of 2010 was somewhat portentous, since my imminent plans to pursue graduate studies in linguistics are leading me to Los Angeles, California. Among other things, it means that the Philadelphia Then and Now posts are coming to an end for the foreseeable future.

When I first created this blog back in 2008, my original intention was to create more of a personal blog with a broader scope of subject matter, which explains the very silly blog name that's now quite out of character with what I've actually written. I suspect that it has to some degree prevented all this from being taken particularly seriously. Anyhow, although I'd been toying with the idea of then and now montages from the beginning, I never imagined that BGTT (thanks for the acronym, Brownstoner!) would become almost exclusively devoted to them. For better or for worse, it's a rather strange yet rewarding addiction.

A great sense of loss accompanies many of the then and now posts that I've done, and I can't see how it could possibly be otherwise. I hope it underscores the urgent need to rediscover, preserve, and protect the many beautiful places that continue to enrich the lives of Philadelphians today. Admittedly, I've only delved into an absolutely minuscule fraction of the region's geographic area and history. I'm reluctantly putting aside a long backlog of Philadelphia places that I never got around to posting about, mostly west of 40th Street, north of Spring Garden, and south of South Street.

I would never have set about blogging were it not for the inspiration I've received from Philadelphia's wonderful blogosphere, and the many great bloggers who have cared so much for this great city's past, present, and future: the beloved and dearly missed Philly Skyline, The Necessity for Ruins, The Illadelph, and the wonderful newcomer Brownstoner, to name just a few. Furthermore, the vast majority of this site would not have been possible without the many repositories of historical images that have graciously made their collections available online, such as the Lower Merion Historical Society, Built in America/HABS, and above all, the amazing PhillyHistory.org. Lastly, I must extend a heartfelt thanks to Professor Jeffrey A. Cohen, who has more than anyone else fostered my fascination with the Philadelphia region's architectural and urban history.

So what happens now? I imagine that I will find the time to continue to write and take photographs in Los Angeles, but probably not for some time after I've settled in. It took me at least two years of living in the Philadelphia area before I could consider myself relatively knowledgeable enough about the region's history to blog about it. I don't think I could properly put into words what an enormous pleasure it has been to live in Philadelphia, and how sad I am to be leaving, so you'll have to take my word for it. So for my readers from the area, thank you so much for supporting the blog, and I do hope you decide to stick around. I'm already looking forward to my next visit.

Tuesday, June 29, 2010

Then and Now: Southeast corner of 8th and Walnut Streets, Philadelphia

Today, the southeast corner of 8th and Walnut Streets is occupied by the base of the St. James apartment tower, completed in 2004 as one of the earliest finished projects in Center City's last residential development boom. In addition to substanially adding to the city skyline east of Broad Street, the project included a significant preservation component. The three remaining houses of York Row (one of which is pictured above) were partially preserved within the tower podium, and are now used as retail and office space. The developers also undertook a full renovation of the adjacent former Pennsylvania Savings Fund Society building facing Washington Square into a large restaurant space.

Not much seems to be known about the one story building at the pictured street corner. However, it appears to have replaced a taller, four story commercial building that occupied the location in the early 20th century.

Photographs:

1. "HABS PA-6661-1." Historic American Buildings Survey. American Memory. Library of Congress. 12 June 2010. http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa3800/pa3816/photos/213253pv.jpg.

2. Mills, Charles P. "Department of City Transit-3820-0." 1917. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 29 Jun. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=38467.

Wednesday, June 23, 2010

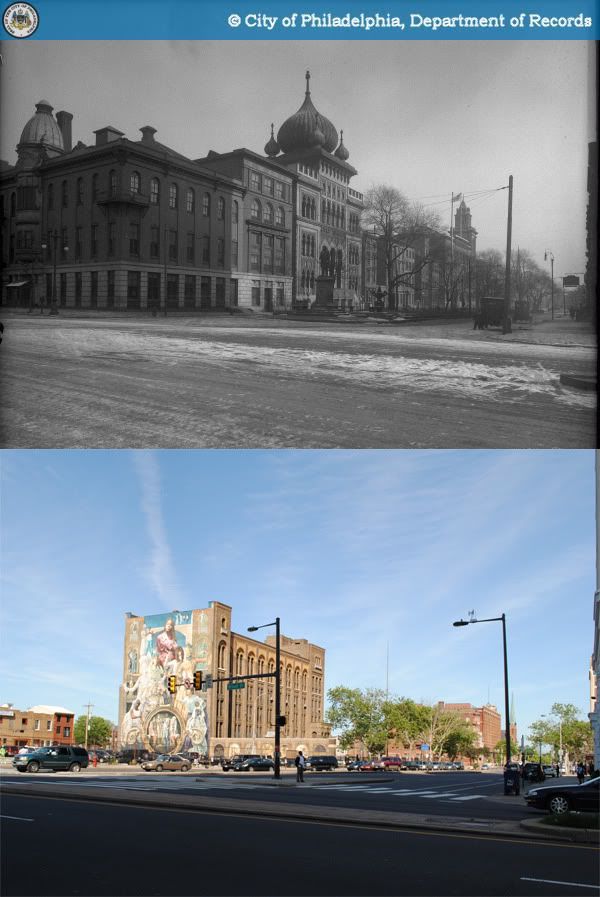

Then and Now: Spring Garden Street east of Broad Street, Philadelphia

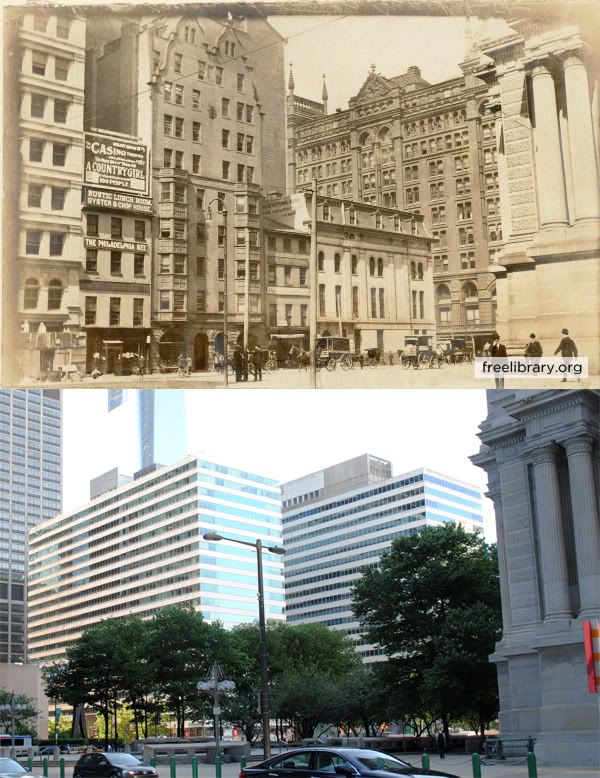

For many decades, the 1300 block of Spring Garden Street was one of Philadelphia's grandest blocks, anchoring the civic and institutional core of lower North Philadelphia. Six years before the consolidation of Philadelphia County into a single municipality, the Spring Garden District built its Commissioner's Hall at the northwest corner of 13th and Spring Garden Streets in 1848. Three years later, the Spring Garden Institute opened its doors at the other end of the block, at the corner of Broad Street. The Commissioner's Hall was demolished in 1892 and replaced by the Philadelphia Normal School for Girls, whose tower is visible in the original photograph.

The onion-domed building adjacent to the Spring Garden Institute is the city's Lu Lu Temple, built in 1904 for the Shriners fraternal order. The Shriners, an offshoot of the Freemasons, were heavily inspired by Middle Eastern traditions, as evident in the Philadelphia temple's design by architect Frederick Webber.

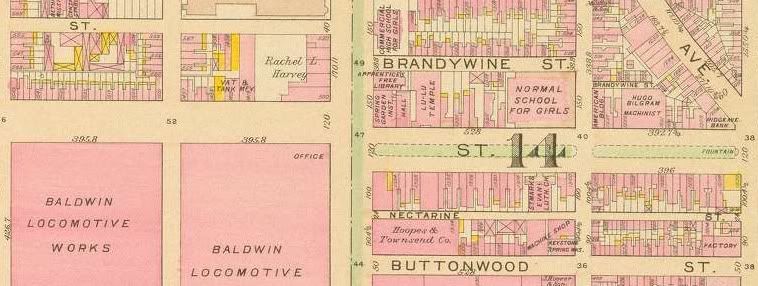

The Broad and Spring Garden intersection in 1910, original atlas image from Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network

The Broad and Spring Garden intersection in 1910, original atlas image from Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory NetworkFor reasons I'm not aware of, the two sections of Spring Garden Street separated by Broad Street were originally not aligned at that intersection; the portion east of Broad terminated roughly 70 feet south of the portion west of Broad. As early as the Civil War, the 1200 and 1300 blocks of Spring Garden were also doted with a spacious and pleasant-looking planted median strip. Real estate atlases seem to indicate that the median was removed sometime around 1920 (perhaps for the construction of the Broad Street Subway).

In 1969, the Spring Garden Institute relocated a new campus in Chestnut Hill, abandoning its original site on Broad Street. Its original buildings, along with the substantially decayed Lu Lu Temple, were demolished in 1972, paving the way for the realigned intersection that stands today.

The only building lucky enough to have survived to this day on the 1301 block of Spring Garden Street is the Philadelphia School District's Stevens Administrative Center, built in 1927.

Sources:

1. Bromley, George W. and Walter S. Atlas of the City of Philadelphia, 1910. G. W. Bromley & Co., 1910. http://www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/view-image.cfm/BRM1910.Phila.001.TitlePage.

2. Calhoun, Chris. "140 Years - A history of practical education." 16 May 2009. Spring Garden College. http://springgardencollege.net/?page_id=12.

3. Khalidi, Omar. "Fantasy, Faith, And Fraternity: American Architecture of Moorish Inspiration." ArchNet. 2004. http://archnet.org/library/documents/one-document.jsp?document_id=9341

Photographs:

1. Biggard, D. Alonzo. "Public Works-37789-0."1941. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 21 Jun. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=21485.

2. "Public Works-11638-0." 1916. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 21 Jun. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=19747.

Thursday, June 17, 2010

Then and Now: Northeast corner of 7th and Market Streets, Philadelphia

The 601 block of Market Street was cleared in the mid-1960s to make way for a federal courthouse and office building complex, occupying the entire site bounded by 6th, 7th, Market, and Arch Streets. Part of the massive Independence Mall urban renewal project, it was designed by a team of architects including Carroll, Grisdale & Van Allen; Stewart, Noble, Class & Partners; and Bellante & Clauss. Completed in 1968, the James A. Byrne Courthouse and William J. Green Federal Building campus suffers from typical design failures of postwar Modernism, such as a barren plaza along 6th Street and long blank walls along its other three sides.

The real tragedy of course, lies in what it replaced - a dense block of mid-rise late 19th century commercial buildings. In terms of scale and architecture, it was not much different from nearby commercial blocks along 5th, 6th, Chestnut, and Arch Streets, once at the heart the city's business district. Unfortunately, extremely little of that area remains today, thanks to ill-conceived urban renewal. Photographs taken just a few years before the block's destruction show few signs of excessive vacancy or deterioration. They hardly suggest a district in irreversible decline, calling into question the alleged necessity for the large scale demolition that took place.

Source: Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

Photographs:

1. Carollo, R. "Department of Public Property-41256-0." 1960. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 17 Jun. 2010. http://phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=143879.

2. Eisenman, George A. "PA-1441-1 - General View of 613-637 Market Street (from right to left), from southwest." 1965. American Memory. Library of Congress. 17 June 2010. http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa0900/pa0988/photos/138970pv.jpg.

Monday, June 14, 2010

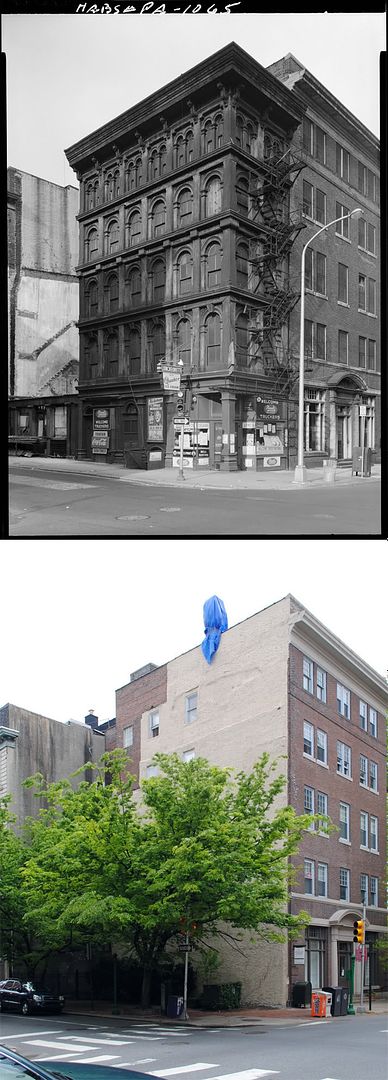

Then and Now: Southwest corner of 3rd and Arch Streets, Philadelphia

On October 13, 1856, a jewelry merchant named George Gordon purchased a four-story warehouse building at 300 Arch Street. By November 20, just over a month later, the original structure had been demolished, and construction had begun on a five-story replacement later known as the George Gordon Building. The Gordon Building is a relatively early work of cast-iron commercial architecture, whose popularity peaked later in the 19th century.

The building had a fairly narrow frontage on Arch Street measuring less than 16 feet (15'-9''). Standing in the pocket park in its place today, it's a bit difficult to imagine that any substantial structure once stood here. After falling into substantial decay, the lot was purchased in 1962 by the Religious Society of Friends, which owned the adjacent 5-story office building at 302-304 Arch Street, as well as the Arch Street Meeting House occupying the rest of the block. The presence of a vacant and deteriorating warehouse adjacent to the Friends' properties posed a growing safety concern, and it was likely for this reason that the Gordon Building was demolished the following year.

A horizontally aligned comparison may be found here.

Source: "George Gordon Building." Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) no. PA,51-PHILA,258. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/habs_haer.

Original photograph: Robinson, Cervin. "PA-1065 - North and east elevations." 1959. Historic American Buildings Survey. American Memory. Library of Congress. 12 June 2010. http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa0700/pa0739/photos/137620pv.jpg.

Tuesday, June 8, 2010

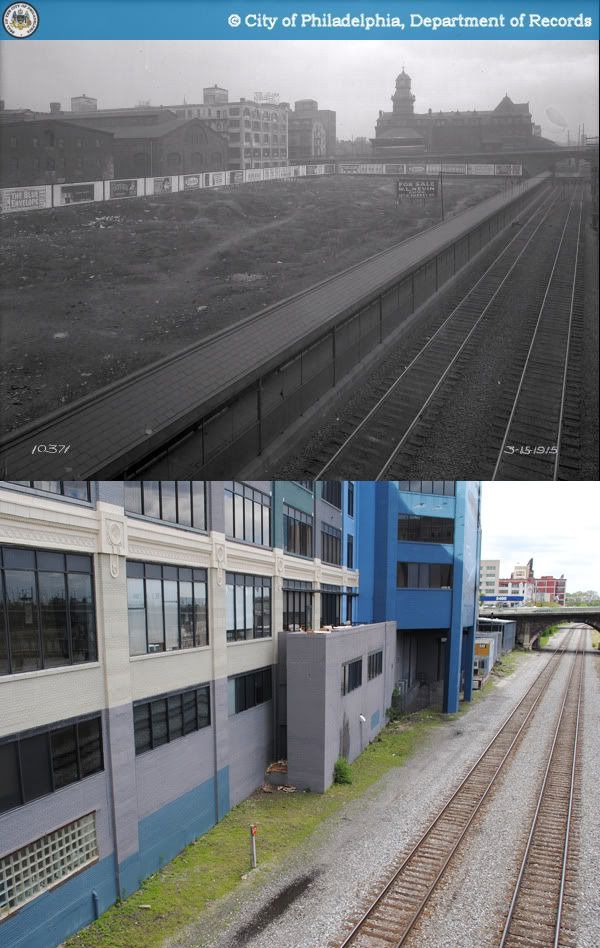

Then and Now: East bank of Schuylkill River at Market Street, Philadelphia

The building on Market Street by the Schuylkill banks that today houses the Marketplace Design Center was initially built as an automobile factory, circa 1920. Like many industrial buildings of its age, it had a loading dock on the ground level connected to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad tracks by a short rail siding. Also visible in the top right of the original photograph is the B&O's passenger terminal at Chestnut Street.

Before the auto factory, this site was occupied a portion of the city's oldest municipal gas works complex, which straddled both sides of Market Street on the Schuylkill River's east bank for most of the 19th century. The facilities between Market and Chestnut Street were demolished around the turn of the century, at which point something very different may have taken its place.

In the 1910s, the empty plot was one of several locations under consideration by the City of Philadelphia for the construction of a much-desired convention hall. The primary advantage of the site was surely not its waterfront locale, but rather its easy accessibility to the growing business district west of Broad Street. Nonetheless, the proposal was discarded by the city in favor of a site on the Parkway, and the riverbank plot was turned to private ownership. As an aside, the Parkway project never got off the ground, and it was not until 1931 that the arduous convention hall saga came to an end with the completion of the Municipal Auditorium in University City.

In the 1910s, the empty plot was one of several locations under consideration by the City of Philadelphia for the construction of a much-desired convention hall. The primary advantage of the site was surely not its waterfront locale, but rather its easy accessibility to the growing business district west of Broad Street. Nonetheless, the proposal was discarded by the city in favor of a site on the Parkway, and the riverbank plot was turned to private ownership. As an aside, the Parkway project never got off the ground, and it was not until 1931 that the arduous convention hall saga came to an end with the completion of the Municipal Auditorium in University City.

(For a detailed account of the perenially sidetracked convention hall project, I highly recommend Sarah Zurier's thesis at the link below)

Source: Zurier, Sarah Elisabeth. "Commerce, Ceremony, Community: Philadelphia's Convention Hall in Context." MS Thesis University of Pennsylvania, 1997. Internet Archive. 8 Jun. 2010. http://www.archive.org/details/commerceceremony00zuri.

Original photographs:

1. "Public Works-10371-0." 1915. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 8 Jun. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=33593.

2. "Public Works-10703-0." 1915. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 8 Jun. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=33703.

Before the auto factory, this site was occupied a portion of the city's oldest municipal gas works complex, which straddled both sides of Market Street on the Schuylkill River's east bank for most of the 19th century. The facilities between Market and Chestnut Street were demolished around the turn of the century, at which point something very different may have taken its place.

(For a detailed account of the perenially sidetracked convention hall project, I highly recommend Sarah Zurier's thesis at the link below)

Source: Zurier, Sarah Elisabeth. "Commerce, Ceremony, Community: Philadelphia's Convention Hall in Context." MS Thesis University of Pennsylvania, 1997. Internet Archive. 8 Jun. 2010. http://www.archive.org/details/commerceceremony00zuri.

Original photographs:

1. "Public Works-10371-0." 1915. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 8 Jun. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=33593.

2. "Public Works-10703-0." 1915. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 8 Jun. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=33703.

Thursday, June 3, 2010

Then and Now: Dock Street west of Second Street, Philadelphia

After being cleared in the early 1960s, this segment of Dock Street as it appears today was rebuilt by the late local real estate developer and film enthusiast, Ramon L. Posel. In 1976, Posel opened the Ritz Three theater at the southwest corner of Dock and Walnut Streets (left of photo), followed in 1977 by a complementary two-story retail building across Dock Street. According to PAB, the retail building was designed by the now obscure architectural firm of Egli & Pratt; I haven't been able to find much on the architects of the Ritz. Nonetheless, both of the glass and brick buildings were designed in a similar style, accented with white steel beams that evoke a certain maritime feel.

Today, Posel's Ritz chain is usually credited with single-handedly building Philadelphia's market for independent and international films. Posel himself was instrumental in crafting the cinema and its mission, and expended significant personal effort to support his brainchild in the face of initial difficulties, for it took seven years for the Ritz Three to turn its first profit. In 1985, the theater was expanded and renamed as the Ritz Five, and the chain continued to grow into the 90s with the openings of the Ritz at the Bourse and the Ritz East. The Ritz chain has certainly been a great success story for urban cinemas during an era where success has generally been the exception to the rule. In 2007, two years after Posel's death, the movie houses were acquired by Landmark Theatres, which has chosen to preserve the Ritz name.

Sources:

1. Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

2. Rickey, Carrie. "Ritz cinema founder Ramon L. Posel dies - Posel's Ritz theaters made region a top art-film destination." Philadelphia Inquirer. 24 Jun. 2005: A01.

3. Van Allen, Peter. "Lamberti's cucina to taste new name, look and menu." Philadelphia Business Journal. 15 Oct. 2004. http://www.bizjournals.com/philadelphia/stories/2004/10/18/story8.html.

Original photo: Cuneo. "Department of Public Property-38863-0." 1959. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 27 Feb. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=141455.

Monday, May 31, 2010

Then and Now: Northwest corner of 8th and Sansom Streets, Philadelphia

Up through the end of the First World War, this corner of Jewelers' Row conserved much of its late Victorian era appearance. Since then, through a series of alterations, the short block has lost many of its original façades and some of its former density. The building with the six-story tower on the far right of the original photo is the Times Building, built for the Times publishing company in the late 1870s and demolished roughly a century later.

Source: Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

Original photo: Mills, Charles P. "Department of City Transit-3829-0." 1917. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 5 Apr. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=38533.

Friday, May 28, 2010

Then and Now: 9-15 East Athens Avenue, Ardmore

In the fight against brick, stucco wins a small victory at Ardmore's Walton Apartments. Not much seems to be known about this humble apartment block, built in the early 1920s. Apparently, those in charge of the building's rehab have decided to replace only the top portion of the brick exterior, while leaving the rest intact (hopefully I'm not mistaken!).

Source: Lower Merion Atlases

Original photo: "9-15 E Athens Ave." Lower Merion/Narberth Buildings. Lowermerionhistory.org. Lower Merion Historical Society. 9 May 2010. http://lowermerionhistory.org/buildings/image-building-list.php?photo_id=6885.

Source: Lower Merion Atlases

Original photo: "9-15 E Athens Ave." Lower Merion/Narberth Buildings. Lowermerionhistory.org. Lower Merion Historical Society. 9 May 2010. http://lowermerionhistory.org/buildings/image-building-list.php?photo_id=6885.

Monday, May 24, 2010

Then and Now: 818-820 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia

Though not quite obvious from its current appearance, this vacant storefront on a quiet block of Chestnut Street gave birth to a true icon of 20th century American dining. In 1902 the Horn & Hardart Baking Company opened their first automat on the ground floor of the Pierson Building at 818-820 Chestnut Street. The automat, where diners purchased food and drink entirely from coin-operated machines, was the first of its kind in the United States. Horn & Hardart expanded rapidly in the decades that followed, developing a legendary presence in Philadelphia and New York before falling into obscurity at the end of the century.

The original Chestnut Street automat was enlarged and renovated during the 1930s, with design work done by architect Ralph Bowden Bencker. During the 20s and 30s, Bencker completed over thirty commissions for Horn & Hardart stores and offices, most of them in Philadelphia. After the original automat shut its doors in the late 1960s, the location operated for some time as a pharmacy. Although the original metalwork has been painted over, the exterior façade appears to be intact, save for the doorway. I've never gone through an exhaustive list of Horn & Hardart's former locations, but it's safe to say that this is certainly one of extremely few preserved storefronts of theirs left in Philadelphia.

Meet me at the automat [Smithsonian magazine]

Source: Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

Original photo: "Historic Commission-12210-48." 1963. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 4 Apr. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=114811.

Thursday, May 20, 2010

Then and Now: Southwest corner of Broad and Walnut Streets, Philadelphia

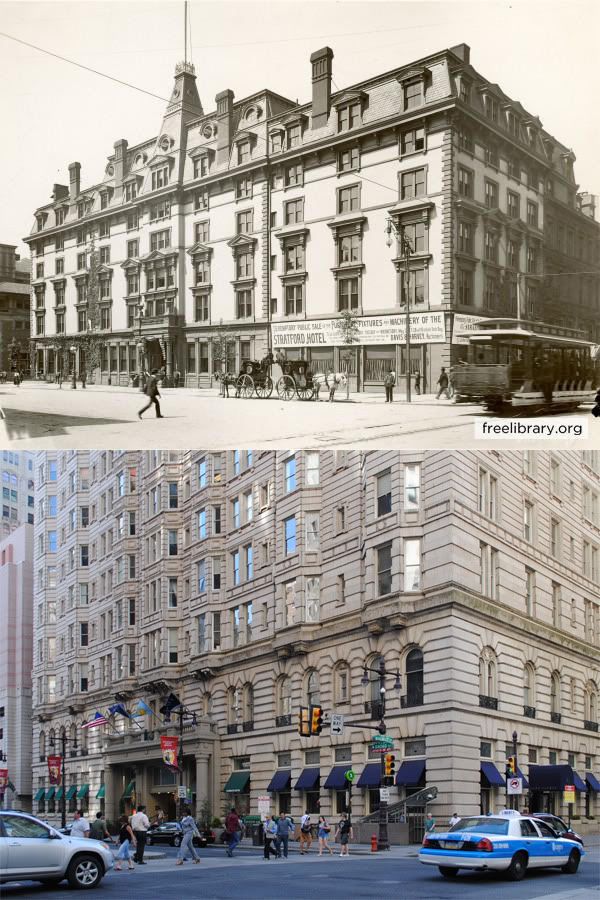

The Stratford Hotel, originally named the Hotel St. George, was built sometime between 1875 and 1885 at the southwest corner of Broad and Walnut Streets. Eventually, the Stratford was acquired by the Hotel Bellevue, a highly successful establishment run by George C. Boldt, located directly across Walnut Street. In 1902, the Stratford Hotel was demolished to make way for Boldt's crowning achievement, the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, a luxurious 20-story Beaux-Arts tower designed by G. W. and W. D. Hewitt, former partners of Frank Furness.

The dramatic differences between the Bellevue-Stratford and its predecessor of two decades, the Stratford, reflect the astonishing growth of Philadelphia at the turn of the century and the ambition and decadence of that era. Despite numerous additions and alterations made since its initial construction, the Bellevue (as it's now called) retains much of its original character, and remains one of South Broad Street's most significant landmarks.

Sources:

1. Bromley, George W. and Walter S. Atlas of the City of Philadelphia, 1885. Philadelphia: G. W. Bromley & Co, 1885. http://philageohistory.org/geohistory/index.cfm.

2. Hopkins, G. M. City Atlas of Philadelphia, Vol. 6, Wards 2 through 20, 29 and 31. Philadelphia: G. M. Hopkins, C. E., 1875. http://philageohistory.org/geohistory/index.cfm.

3. Thomas, George E. "National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form: Bellevue Stratford Hotel." 1976. National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. 20 May 2010. http://www.arch.state.pa.us/pdfs/H001328_01B.pdf.

Original photo: Jennings, W.K. "PDCL00172." Free Library - Historical Images of Philadelphia. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 19 May 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=166757.

Sunday, May 16, 2010

Then and Now: Corner of 32nd and Market Streets looking northeast, Philadelphia

At the time of the Second World War, the Market-Frankford Line was fully elevated through West Philadelphia, emerging from the subway tunnel at 22nd and Market Streets. The original photograph shows part of the original "El" station at 32nd Street, completed in 1908. Barely visible in the background of the original photo is the Pennsylvania Railroad's West Philadelphia Station, which at the time was the city's main railroad station west of the Schuylkill River. West Philadelphia Station was demolished after the opening of 30th Street Station in 1933.

During the war, the City of Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Transit Company (PTC) initiated a major project to extend the Market Street subway tunnel from 22nd Street past 40th Street. Furthermore, the PTC's West Philadelphia trolley lines would be rerouted into a subway tunnel below Woodland Avenue, joining the Market Street Subway tunnel at 32nd Street. Due to the relocation of the Pennsylvania Railroad station to 30th Street, the new Market-Frankford Line stations were built at 30th and 34th Streets, neither of which were previously station stops. The transit tunnels opened in 1955, and the obsolete elevated rails and stations were removed the following year.

About a decade ago, Drexel University annexed the block of 32nd Street between Market and Chestnut Streets, and has since developed it into a landscaped pedestrian walkway.

Market-Frankford Line [nycsubway]

Source: Darlington, Peggy, Gregory Jordan-Detamore, and David Pirmann. "Market-Frankford El." world.nycsubway.org. 12 May 2010. http://world.nycsubway.org/us/phila/market-frankford.html.

Original photo: Quinn. "Department of City Transit-20601-0." 1930. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 12 May 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=19505.

Thursday, May 13, 2010

Then and Now: Market Street west of 11th Street, Philadelphia

Originally located at the corner of 5th and South Streets, the N. Snellenberg & Co. department store moved to Market East at the turn of the 20th century. At its height, the Snellenberg's department store occupied a full block of Market Street between 11th and 12th Streets, across from Reading Terminal.

Snellenberg's was one of the earliest of Market East's large department stores to collapse, going out of business in 1963. Although the Community College of Philadelphia opened in 1965 in the mens department annex at 34 South 11th Street, the Market Street buildings remained vacant. To cut down on maintenance costs, the Girard Estate, which has owned the property since the early 19th century, removed all but the bottom two stories of the six-story buildings, unifying their facades under a modernist exterior.

Source: Warner, Susan. "What's in store in Center City?" Philadelphia Inquirer. 26 Apr. 1999: F01.

Original photo: Carollo, R. "Historic Commission-2648-1." 1965. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 10 May 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=106691.

Tuesday, May 11, 2010

Then and Now: West side of Penn Square, Philadelphia

For the first half of the 20th century, Broad Street veered off of its linear path at City Hall, snaking around the west side of the public buildings on what could otherwise have been called "West Penn Square." A decade after the original photograph was taken, the four buildings facing Broad Street from the left edge of the photo had been demolished to make way for the Commercial Trust Building (aka Arcade Building), a behemoth structure occupying nearly the entire block bounded by 15th St., Broad St., Market St., and South Penn Square.

After the demolition of Broad Street Station in 1953, the Planning Commission envisioned an extension of City Hall's plaza from Broad Street to 15th Street. Two and Three Penn Center, the twin office buildings featured prominently in today's view, were built west of 15th Street. The Arcade Building was not demolished until 1969, paving the way for a concrete plaza and subterranean transit concourse completed in 1977, now known as Dilworth Plaza. If the Center City District has its way, the oft-maligned public space may receive a dramatic makeover in the next few years.

Center City Reports: Transforming Dilworth Plaza [Center City District]

Source: Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

Original photographs:

1. "PDCL00160." 1903. Free Library of Philadelphia - Historical Images of Philadelphia. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 10 May 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=166729.

2. Boucher, Jack. "PA-1493-1 - General view, from east." 1962. Historic American Buildings Survey. Library of Congress. 10 May 2010. http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa1000/pa1083/photos/139988pv.jpg.

Sunday, May 9, 2010

Then and Now: Baltimore & Ohio Railroad station, 24th and Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia

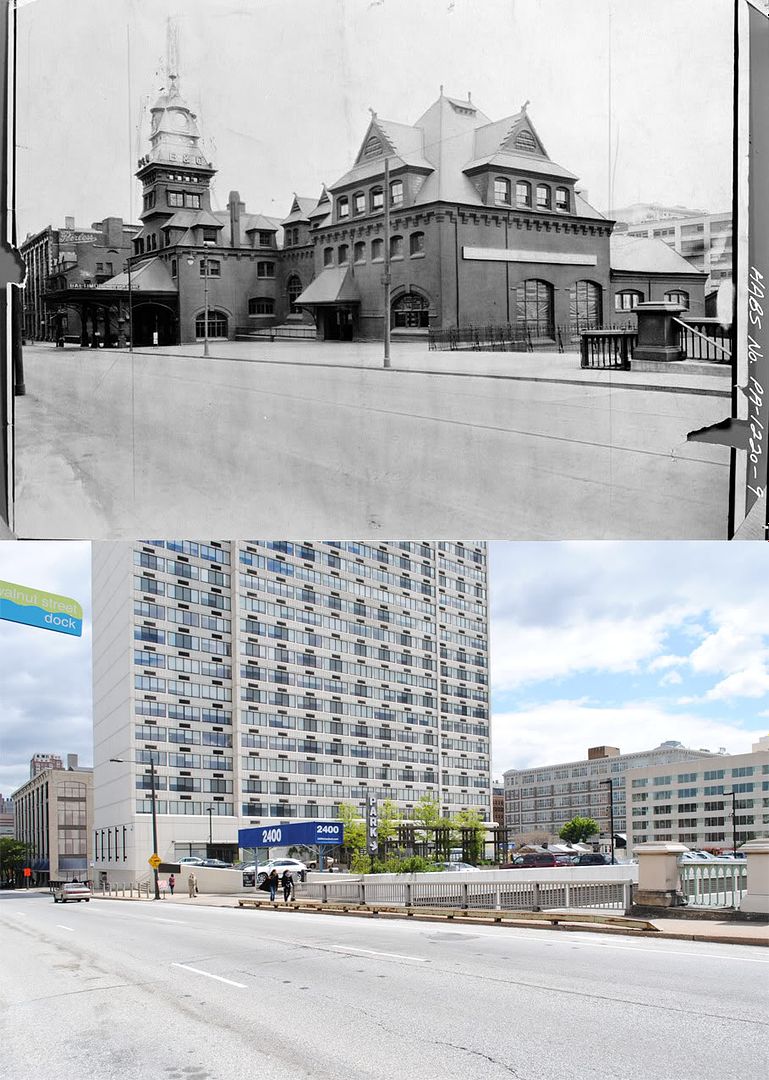

The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad entered Philadelphia's rapidly-growing passenger rail market in the late-19th century, opening its own passenger terminal in 1888 at 24th and Chestnut Streets, at the foot of the Chestnut Street Bridge. The station was designed by none other than the prolific Furness, Evans, & Co., who went on the build the much grander expansion to Broad Street Station just a few years later. Perhaps owing to the station's less than ideal location and relatively minuscule size, it never quite achieved the landmark status attained by the city's other two Center City terminals, Broad Street Station and Reading Terminal.

Passenger service ended along the Baltimore & Ohio line in the late 1950s, and the Philadelphia station was demolished in 1963. The building's former site stood vacant for over a decade before the completion of a 34-story apartment tower, 2400 Chestnut, in 1979. Through a number of acquisitions and mergers, the remnants of the B&O are now part of CSX Transportation, a freight company which continues to operate the railroad's tracks along the Schuylkill.

Some more tidbits on 2400 Chestnut [Philly Skyline]

Sources:

1. "2400 Chestnut Apartments, Philadelphia, U.S.A." Emporis.com. 8 May 2010. http://www.emporis.com/application/?nav=building&lng=3&id=2400chestnutapartments-philadelphia-pa-usa.

2. Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

Original photos:

1. "PA-1220-7 - Photocopy of photograph: Perspective view of north and east elevations." Historic American Buildings Survey. American Memory. Library of Congress. 8 May 2010. http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa1000/pa1097/photos/138632pv.jpg.

2. "PA-1220-9 - View from north west, closeup of station." Historic American Buildings Survey. American Memory. Library of Congress. 8 May 2010. http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa1000/pa1097/photos/138634pv.jpg.

Tuesday, May 4, 2010

Then and Now: East bank of Schuylkill River from Chestnut Street Bridge, Philadelphia

In 1928, the lower end of the Schuylkill River running through Center City Philadelphia was not exactly an inviting place to linger. Between Spring Garden Street and Spruce Street, the river's east bank was lined with freight depots, warehouses, and factories, while the west bank was home to an enormous stockyard and abbattoir. To top it off, much of the city's untreated sewage was dumped directly into the river via over twenty mains placed by the Fairmount Dam, turning the Schuylkill into an enormous cesspool.

As the 20th century progressed, the lower Schuylkill slowly shed its grimy, industrial character. The current Market Street Bridge replaced its iron predecessor in 1932. Shortly afterward, the west bank was wholly transformed after the stockyards were replaced by 30th Street Station and the adjacent U.S. Post Office. In the 1950s and 1960s, the city made great strides toward completing its sewage treatment network, vastly improving the river's water quality. One by one, the freight yards and warehouses along the east bank closed under the forces of deindustrialization. The Hudson Essex automobile factory (pictured above) shut its doors, reopening as the Marketplace Design Center, a design showroom, in 1975.

Forward-looking Philadelphians had in fact dreamed of a riverfront park on the lower Schuylkill's east bank as early as the 1920s. Concrete development plans emerged for the first time in the late 1960s, but came to a grinding halt before being revived nearly 30 years later. In 1995, the City of Philadelphia began finally began construction of a segment of the Schuylkill River Trail between Kelly Drive and Locust Street. Originally scheduled for completion in 1997, spectacular delays and legal battles postponed the park's official opening to 2004.

Sources:

1. Demick, Barbara. "The Marketplace: its doors open by invitation only." Philadelphia Inquirer. 11 Jul. 1988: D01.

2. Heavens, Alan J. "Schuylkill Park ready to bloom." Philadelphia Inquirer. 4 Jun. 1995: R01.

3. Lewis, John Frederick. The Redemption of the Lower Schuylkill. Philadelphia: The City Park Association, 1924.

4. Saffron, Inga. "A fine park now, and even better later - the Schuylkill parks' present, promise." Philadelphia Inquirer. 25 Jun. 2004: E01.

Original photo: "CPA1146 - East bank of the Schuylkill from Chestnut Street Bridge." 1928. City Parks Association Photographs. Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives. 1 May 2010. http://digital.library.temple.edu/u?/p15037coll5,208.

Saturday, May 1, 2010

Then and Now: Southwest corner of 10th and Arch Streets, Philadelphia

While the altered facades on the two corner buildings pictured are lamentable, one should perhaps be grateful that they are still standing at all. On May 3, 1984, flames broke out during renovation work for the Harrison Court building at 10th and Filbert (bottom left of original photo). Miraculously, only two people were treated for injuries from the conflagration. The fire however, largely destroyed the 1000 block of Filbert Street, inadvertently clearing the way for what is now the city's Greyhound bus terminal.

Gibbons, Thomas J., L. Stuart Ditzen, and Hank Klibanoff. "9-alarm fire hits Center City - 18 buildings burn." Philadelphia Inquirer. 4 May 1984: A01.

Monday, April 26, 2010

Then and Now: South Street east of Third Street, Philadelphia

On the left hand side of today's view is Abbott's Square, a gargantuan condominium complex spanning a full block of South Street and Second Street. Built in the mid-1980s, Abbott's Square takes its name from Abbott's Dairies, which operated a nearby ice cream factory on the 200 block of Lombard Street before closing in 1982.

As in most of the city, trolley service on South Street ended in the late 50s; the tracks and wires were removed shortly thereafter.

Source: Thompson, Gary. "Finally, a first step at Penn's Landing: $35M project, long in the works, could spark a renaissance." Philadelphia Daily News. 2 Jan. 1985: 23.

Original photo: Howell, Charles L. "Public Works-28458-0." 1930. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 23 Apr. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=37897.

Friday, April 23, 2010

Then and Now: Betsy Ross House, 239 Arch Street, Philadelphia

As far as museums go, the Betsy Ross House is one of Philadelphia's oldest, and has been at least partially open to the public since 1898. The building went through a major renovation in 1937, which included a redesigned facade designed by Colonial Revival specialist Richardson Brognard Okie. Shortly afterward, the former warehouse properties on its western side were demolished and replaced with a new courtyard for the museum. The Berger Brothers warehouse on the other side was demolished sometime after 1964, giving the 18th-century house even more "breathing room."

A quick history of the building [Betsy Ross House]

The original (extremely hi-res) image [Shorpy]

Original photo: Detroit Photographic Company. "012944-Betsy Ross House, Philadelphia." 1900. Shorpy Historic Photo Archive. 22 Apr. 2010. http://www.shorpy.com/files/images/4a08439a.jpg.

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

Then and Now: The Merchants Exchange viewed from Dock Street, Philadelphia

The Merchants Exchange was commissioned in 1831 by the Philadelphia Exchange Company, a group of prominent merchants who had organized for the purpose of building a main brokerage hall for Philadelphia's fast-growing commercial center. Built between the city's waterfront and its banking district on Chestnut Street, the Exchange stood at the very epicenter of Philadelphia's commercial core for the four decades that followed. The building was also the last major commission in Philadelphia awarded to William Strickland, a preeminent figure in the development of Greek Revival architecture in the United States. Thanks in part to its irregular plot at the corner of Walnut and Dock Streets, Strickland's original design included a striking semi-circular portico on its eastern facade, topped off with a lantern replicating the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens.

The building changed hands several times in the first century of its life, undergoing multiple interior and exterior alterations. Upon its repurchase by the Philadelphia Stock Exchange in 1901, the lantern was dismantled and a redesigned version was built somewhat to the east of its original location. In 1922, long after Philadelphia's center of business had moved to Broad Street, it joined Dock Street's produce market as the Produce Exchange, and ground floor sheds were added to its eastern facade.

In 1952, the building came under the ownership of the National Park Service, which removed the produce sheds and began a full renovation of the building's exterior. Several years later, the 1901 lantern was dismantled and replaced by a replica of the original in its original location. The former Merchants Exchange is now used as offices for the Park Service.

Few of the Exchange's immediate neighbors in 1939 were fortunate enough to survive the rest of the 20th century. Only one other building visible in the original photo still stands today, the First Bank of the United States on Third Street.

Source: Zana C. Wolf and Charles Tonetti. "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Merchants' Exchange Building." 2000. National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. 20 Apr. 2010. http://www.nps.gov/nhl/designations/samples/pa/MEB.pdf.

Original photo: Nichols, Frederick D. "PA-1028-1-General View." 1939. Historic American Buildings Survey. American Memory. The Library of Congress. 20 Apr. 2010. http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa1000/pa1045/photos/137107pv.jpg.

Friday, April 16, 2010

Then and Now: The Trans-Lux Theater, 1519 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia

1935-2010

1935-2010The Trans-Lux Theater first opened in 1934 as a newsreel theater, one of the many cinemas that once lined Chestnut Street west of Broad. Its design is attributed to the prolific American theater architect Thomas W. Lamb, best known for his classical revival theater designs from the 1910s and 20s. However, as the Trans-Lux attests, he managed to transition masterfully into Art Deco during the later years of his career.

Tragically, in 1970, the theater's facade was completely rebuilt before its reopening as the Eric's Place Theatre. Oddly enough, the renovations were done by an 85-year-old William Harold Lee, himself a prominent Philadelphian theater architect. It is simply unfathomable to me how he could have consented to the destruction of the Lamb's exquisite design.

Chestnut Street's beleaguered row of movie houses collapsed in the early 1990s; Eric's Place closed in 1993 and reopened in 2006 as an athletics shoe store.

A photograph of the shuttered Eric's Place Theatre [HowardBHaas on Flickr]

Source: Bryan and Howard B. Haas. "Eric's Place Theatre." Cinema Treasures. 15 Apr. 2010. http://cinematreasures.org/theater/9143/.

Original photo: Gee, William A. "Public Works-35005-0." 1935. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 15 Apr. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=15929.

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

Then and Now: North side of Sansom Street, west of no. 735 Sansom, Philadelphia

1931-2010

1931-2010The ground-floor storefronts on this corner of Sansom Street have been completely rebuilt since the 1930s. If you look closely at the grooves of the sidewalk curb however, you will find that it remains essentially unchanged.

Original photo: Sack. "Department of City Transit-22539-0." 1931. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 8 Apr. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=39707

Friday, April 9, 2010

Unbuilt Philadelphia: Twin towers at the Gallery II

Hot on the heels of the opening of the Gallery in 1977, the second major phase of the city's Market East redevelopment plan began to take shape. In 1978, the city began construction of the epic $325 million Center City Commuter Tunnel, including the underground Market East Station. The new commuter rail station was to be connected to the original Gallery by the Gallery II, a major expansion of the bunker-like shopping mall from 10th to 11th Streets, also developed by the Rouse Company.

Hot on the heels of the opening of the Gallery in 1977, the second major phase of the city's Market East redevelopment plan began to take shape. In 1978, the city began construction of the epic $325 million Center City Commuter Tunnel, including the underground Market East Station. The new commuter rail station was to be connected to the original Gallery by the Gallery II, a major expansion of the bunker-like shopping mall from 10th to 11th Streets, also developed by the Rouse Company.One of the more ambitious components of the original plan was the eventual construction of two twin office towers rising on top of the Gallery II, pictured above in a rendering from 1979. The planned towers would have risen over 20 stories, providing up to 440,000 square feet of new office space at the northwest corner of 10th and Market (above the former site of the Harrison Building).

Since engineering work for the Gallery II anticipated the office tower complex, construction proceeded on the new shopping mall in the early 80s while the city negotiated with potential developers. However, the Gallery II struggled to attract its anticipated customers after its rainy opening day in 1983, and never lived up to the Rouse Company's nor the city's expectations. Furthermore, repeated efforts to sell the building's air rights throughout the decade were ultimately unsuccessful. The last serious push came and went in 1993, when the site above the Gallery II was one of four locations under consideration for the consolidated offices of SEPTA, which ultimately took up residence at 1234 Market Street.

The story isn't over, however. The structural engineering of the Gallery II remains in place, and the Market East Strategic Plan released last year by the Planning Commission points out the ongoing potential for high-density development above the mall. Over three decades after its conception, this dream for Market East has yet to completely fade to dust.

Sources:

1.Brown, Jeff. "SEPTA's search for a new home: major stakes and twisted arms - The Redevelopment Authority has a proposal." Philadelphia Inquirer. 7 Mar. 1993: C01.

2. Kennedy, Sara. "The tunnel: mud to steel - on schedule and grinding ahead quietly." Philadelphia Inquirer. 14 Nov. 1982: B01.

3. Lin, Jennifer. "Opening day - despite rain, a festive air reigns at Gallery II. " Philadelphia Inquirer. 13 Oct. 1983: B01.

Image: "P086218 - Drawing of office complex to be built over Gallery II." 1979. Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Photographs. Temple University Library, Urban Archives. 6 Apr. 2010.

http://digital.library.temple.edu/u?/p15037coll3,1727.

Wednesday, April 7, 2010

Then and Now: Southeast corner of 8th and Sansom Streets, Philadelphia

The Jewelry Trades Building was built c. 1930 on the site of four lots on the western end of the block of Sansom Street now known as Jewelers' Row. The architect, Ralph Bowden Bencker, was one of Philadelphia's more prolific early Modernist architects in the 1920s and 30s, best known for designing the Rittenhouse Plaza apartments and the Ayer on Washington Square. The Jewelry Trades Building is fairly representative of Bencker's architectural style, which can generally be characterized as a minimalist, monochrome Art Deco.

Mills, Charles P. "Department of City Transit-3822-0." 1917. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 5 Apr. 2010. http://phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=44373.

Monday, April 5, 2010

Construction update: Drexel Recreation Center

There's been such a general dearth of new construction here in the past few months that I'd even lost track of the handful of mid-sized projects nearing completion. The opening of Drexel's new Recreation Center back in February flew right under the radar, but I managed to finally get a look at the completed product over the weekend.

Designed by Sasaki Associates with engineering work by EwingCole and Pennoni, the 84,000 square foot building occupies an entire block of Market Street between 33rd and 34th Streets, wrapping around the existing Daskalakis Athletics Center and replacing what was previously a perimeter of inactive and unused open space.

As far as university campus additions go, the Recreation Center was highly anticipated. For Drexel planners, it provided another essential step toward shedding the university's reputation as a hotspot of orange brick and mediocre modernism. The wise decision to wrap the new building around the Daskalakis Athletics Center was not only cost effective for Drexel, but also provided a rare opportunity to breathe new life into a particularly quiet stretch of Market Street. To that end, the ground floor of the building also houses a newly opened restaurant and bar occupying half of the building's Market Street frontage, providing another amenity for the campus and nearby area.

As far as university campus additions go, the Recreation Center was highly anticipated. For Drexel planners, it provided another essential step toward shedding the university's reputation as a hotspot of orange brick and mediocre modernism. The wise decision to wrap the new building around the Daskalakis Athletics Center was not only cost effective for Drexel, but also provided a rare opportunity to breathe new life into a particularly quiet stretch of Market Street. To that end, the ground floor of the building also houses a newly opened restaurant and bar occupying half of the building's Market Street frontage, providing another amenity for the campus and nearby area.

Personally, I find the the window patterning of the upper stories to be visually interesting. Nonetheless, the building's ground floor presence leaves a lot to be desired. The non-restaurant half of the Market Street frontage hides a large lounge space behind a very opaque band of windows. Contrary to the project's intentions and expectations, the pedestrian experience along this block is decidedly a bit dull, albeit a definite improvement over previous conditions. Another lesson learned: windows are never as transparent as promised by architectural renderings.

Perhaps such judgments are somewhat premature, given the continued presence of orange construction cones around the site. However, there are a few simple changes that could greatly improve the building's interaction with its neighbors. The presence of the Market Street Subway beneath the roadway probably precludes the planting of street trees. Nonetheless, the sidewalk is virtually crying out for at least some plantings and shade, a need which will only become more evident with the approach of summer. Lastly, I will also suggest that the ground floor facade could be significantly enlivened by some sort of engaging display or signage without compromising the quality of the building's interior spaces.

Perhaps such judgments are somewhat premature, given the continued presence of orange construction cones around the site. However, there are a few simple changes that could greatly improve the building's interaction with its neighbors. The presence of the Market Street Subway beneath the roadway probably precludes the planting of street trees. Nonetheless, the sidewalk is virtually crying out for at least some plantings and shade, a need which will only become more evident with the approach of summer. Lastly, I will also suggest that the ground floor facade could be significantly enlivened by some sort of engaging display or signage without compromising the quality of the building's interior spaces.

Recreation Center opening press release [Drexel University]

Designed by Sasaki Associates with engineering work by EwingCole and Pennoni, the 84,000 square foot building occupies an entire block of Market Street between 33rd and 34th Streets, wrapping around the existing Daskalakis Athletics Center and replacing what was previously a perimeter of inactive and unused open space.

As far as university campus additions go, the Recreation Center was highly anticipated. For Drexel planners, it provided another essential step toward shedding the university's reputation as a hotspot of orange brick and mediocre modernism. The wise decision to wrap the new building around the Daskalakis Athletics Center was not only cost effective for Drexel, but also provided a rare opportunity to breathe new life into a particularly quiet stretch of Market Street. To that end, the ground floor of the building also houses a newly opened restaurant and bar occupying half of the building's Market Street frontage, providing another amenity for the campus and nearby area.

As far as university campus additions go, the Recreation Center was highly anticipated. For Drexel planners, it provided another essential step toward shedding the university's reputation as a hotspot of orange brick and mediocre modernism. The wise decision to wrap the new building around the Daskalakis Athletics Center was not only cost effective for Drexel, but also provided a rare opportunity to breathe new life into a particularly quiet stretch of Market Street. To that end, the ground floor of the building also houses a newly opened restaurant and bar occupying half of the building's Market Street frontage, providing another amenity for the campus and nearby area.Personally, I find the the window patterning of the upper stories to be visually interesting. Nonetheless, the building's ground floor presence leaves a lot to be desired. The non-restaurant half of the Market Street frontage hides a large lounge space behind a very opaque band of windows. Contrary to the project's intentions and expectations, the pedestrian experience along this block is decidedly a bit dull, albeit a definite improvement over previous conditions. Another lesson learned: windows are never as transparent as promised by architectural renderings.

Perhaps such judgments are somewhat premature, given the continued presence of orange construction cones around the site. However, there are a few simple changes that could greatly improve the building's interaction with its neighbors. The presence of the Market Street Subway beneath the roadway probably precludes the planting of street trees. Nonetheless, the sidewalk is virtually crying out for at least some plantings and shade, a need which will only become more evident with the approach of summer. Lastly, I will also suggest that the ground floor facade could be significantly enlivened by some sort of engaging display or signage without compromising the quality of the building's interior spaces.

Perhaps such judgments are somewhat premature, given the continued presence of orange construction cones around the site. However, there are a few simple changes that could greatly improve the building's interaction with its neighbors. The presence of the Market Street Subway beneath the roadway probably precludes the planting of street trees. Nonetheless, the sidewalk is virtually crying out for at least some plantings and shade, a need which will only become more evident with the approach of summer. Lastly, I will also suggest that the ground floor facade could be significantly enlivened by some sort of engaging display or signage without compromising the quality of the building's interior spaces.Recreation Center opening press release [Drexel University]

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Then and Now: Charles C. Harrison Building, Northwest corner of 10th and Market Streets, Philadelphia

The Charles C. Harrison Building at 10th and Market Streets was commissioned in 1893 by Charles Custis Harrison, a Philadelphia-born industrialist who had amassed a significant fortune as one of the founders of the Franklin Sugar Refining Company. The architects, the nascent Philadelphia firm of Cope & Stewardson, had recently completed a number of campus buildings for Bryn Mawr College. Interestingly, both parties were destined to spend their next few decades working in the milieu of academia.

In 1895, Harrison was inaugurated as Provost of the University of Pennsylvania, a position which he held until his resignation in 1910. During his tenure, Cope & Stewardson were recruited for six of the University's major campus additions - including the Quadrangle and Law School buildings. During that time, the firm was also awarded a number of major commissions at Washington University in St. Louis and subsequently, Princeton University. Today, the firm is best remembered for its many contributions to American collegiate architecture, and the Charles C. Harrison Building was one of only five commercial structures ever designed by their practice.

The Harrison Building changed hands multiple times and went through several exterior and interior alterations during its lifetime. In 1941, the first two floors of the exterior were wrapped under a white marble facade, shown in the photo above. In 1978, the structure was condemned by the city's Redevelopment Authority for the westward expansion of The Gallery at Market East and the construction of Market East Station. The building was demolished the following year, and The Gallery II opened in its place in 1984.

A vertically aligned comparison may be found here.

Sources:

1. "Charles C. Harrison Building, 1001-1005 Market Street." Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. PA,51-PHILA,520. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hh:1:./temp/~ammem_DRuX::.

2. Joyce, J. St. George, ed. Story of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Harry B. Joseph, 1919. Google Books. 30 Mar. 2009.

Original photo: James L. Dillon & co., inc. "PA-550-2: South (front) and east elevations." 1979. Historic American Buildings Survey. American Memory. The Library of Congress. 30 Mar. 2010. http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa0800/pa0809/photos/138979pv.jpg.

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Then and Now: Independent Order of Odd Fellows Hall, Northwest corner of Third and Brown Streets, Philadelphia

The few extremely loyal readers of this blog may remember a very early post of mine featuring this same exact corner, whose history I was unable to find at the time. It would not have been such a mystery at all had I simply known where to look. Thankfully, as it is for all occupations, with time comes experience, and it is with great pleasure that I now return to this corner of Northern Liberties.

The building that once stood at the northwest corner of 3rd and Brown Streets was completed in 1846 as an Independent Order of Odd Fellows Hall, designed in an Egyptian Revival style that was then enjoying a brief period of popularity. Though only four stories tall, the Odd Fellows Hall was certainly an imposing presence among its neighbors. Especially distinctive were the ten bays of its east and south elevations, composed of three-story vertical window bands embedded within large pilasters. This majestic emphasis on verticality is in some ways quite reminiscent of the much later style of Art Deco. The pilasters and roof cornice were apparently painted in a dark red color, and the remaining exterior walls were covered by tan-colored plaster.

Had the Odd Fellows Hall survived to this day, it would have been one of the only remaining examples of Egyptian Revival architecture in Philadelphia, and one of a handful left in the United States. Despite the rapid expansion of the Odd Fellows' organization in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the fraternal society held on to their Northern Liberties site as late as 1922. However, by the time of its Historic American Buildings Survey documentation in 1961, the building's ground floor had long been gutted and converted to warehouse space (for J. Friedman Fruit & Produce Packages), while its upper stories remained vacant. After 130 years of existence, the former Odd Fellows Hall was destroyed by fire in 1976.

A vertically aligned comparison may be found here.

Sources:

1. Bromley, George W. and Walter S Bromley. Atlas of the City of Philadelphia (Central). Philadelphia: G. W. Bromley & Co, 1922. http://philageohistory.org/geohistory/index.cfm.

2. Independent Order of Odd Fellows, Third & Brown Streets. Historic American Building Survey HABS No. PA-1771. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hh:1:./temp/~ammem_touu::.

Original photo: Boucher, Jack B. "PA-1771-1: Exterior view from southeast, showing east (right) and south (left) elevations." 1961. Historic American Buildings Survey. American Memeory. The Library of Congress. 23 Mar. 2010. http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa0800/pa0858/photos/138362pv.jpg.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)