Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Then and Now: Charles C. Harrison Building, Northwest corner of 10th and Market Streets, Philadelphia

The Charles C. Harrison Building at 10th and Market Streets was commissioned in 1893 by Charles Custis Harrison, a Philadelphia-born industrialist who had amassed a significant fortune as one of the founders of the Franklin Sugar Refining Company. The architects, the nascent Philadelphia firm of Cope & Stewardson, had recently completed a number of campus buildings for Bryn Mawr College. Interestingly, both parties were destined to spend their next few decades working in the milieu of academia.

In 1895, Harrison was inaugurated as Provost of the University of Pennsylvania, a position which he held until his resignation in 1910. During his tenure, Cope & Stewardson were recruited for six of the University's major campus additions - including the Quadrangle and Law School buildings. During that time, the firm was also awarded a number of major commissions at Washington University in St. Louis and subsequently, Princeton University. Today, the firm is best remembered for its many contributions to American collegiate architecture, and the Charles C. Harrison Building was one of only five commercial structures ever designed by their practice.

The Harrison Building changed hands multiple times and went through several exterior and interior alterations during its lifetime. In 1941, the first two floors of the exterior were wrapped under a white marble facade, shown in the photo above. In 1978, the structure was condemned by the city's Redevelopment Authority for the westward expansion of The Gallery at Market East and the construction of Market East Station. The building was demolished the following year, and The Gallery II opened in its place in 1984.

A vertically aligned comparison may be found here.

Sources:

1. "Charles C. Harrison Building, 1001-1005 Market Street." Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. PA,51-PHILA,520. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hh:1:./temp/~ammem_DRuX::.

2. Joyce, J. St. George, ed. Story of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Harry B. Joseph, 1919. Google Books. 30 Mar. 2009.

Original photo: James L. Dillon & co., inc. "PA-550-2: South (front) and east elevations." 1979. Historic American Buildings Survey. American Memory. The Library of Congress. 30 Mar. 2010. http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa0800/pa0809/photos/138979pv.jpg.

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Then and Now: Independent Order of Odd Fellows Hall, Northwest corner of Third and Brown Streets, Philadelphia

The few extremely loyal readers of this blog may remember a very early post of mine featuring this same exact corner, whose history I was unable to find at the time. It would not have been such a mystery at all had I simply known where to look. Thankfully, as it is for all occupations, with time comes experience, and it is with great pleasure that I now return to this corner of Northern Liberties.

The building that once stood at the northwest corner of 3rd and Brown Streets was completed in 1846 as an Independent Order of Odd Fellows Hall, designed in an Egyptian Revival style that was then enjoying a brief period of popularity. Though only four stories tall, the Odd Fellows Hall was certainly an imposing presence among its neighbors. Especially distinctive were the ten bays of its east and south elevations, composed of three-story vertical window bands embedded within large pilasters. This majestic emphasis on verticality is in some ways quite reminiscent of the much later style of Art Deco. The pilasters and roof cornice were apparently painted in a dark red color, and the remaining exterior walls were covered by tan-colored plaster.

Had the Odd Fellows Hall survived to this day, it would have been one of the only remaining examples of Egyptian Revival architecture in Philadelphia, and one of a handful left in the United States. Despite the rapid expansion of the Odd Fellows' organization in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the fraternal society held on to their Northern Liberties site as late as 1922. However, by the time of its Historic American Buildings Survey documentation in 1961, the building's ground floor had long been gutted and converted to warehouse space (for J. Friedman Fruit & Produce Packages), while its upper stories remained vacant. After 130 years of existence, the former Odd Fellows Hall was destroyed by fire in 1976.

A vertically aligned comparison may be found here.

Sources:

1. Bromley, George W. and Walter S Bromley. Atlas of the City of Philadelphia (Central). Philadelphia: G. W. Bromley & Co, 1922. http://philageohistory.org/geohistory/index.cfm.

2. Independent Order of Odd Fellows, Third & Brown Streets. Historic American Building Survey HABS No. PA-1771. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hh:1:./temp/~ammem_touu::.

Original photo: Boucher, Jack B. "PA-1771-1: Exterior view from southeast, showing east (right) and south (left) elevations." 1961. Historic American Buildings Survey. American Memeory. The Library of Congress. 23 Mar. 2010. http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa0800/pa0858/photos/138362pv.jpg.

Friday, March 19, 2010

Then and Now: Northwest corner of 10th and Arch Streets, Philadelphia

1960-2010

1960-2010The corner of 10th and Arch Streets now boasts two of Chinatown's most important landmarks. The Trocadero Theatre at 1003-1005 Arch Street was first built as the Arch Street Opera House in 1870, designed by Edwin Forrest Durang, known primarily as an architect of Catholic churches. In its 140-year history, the theater has gone through at least 11 name changes and multiple interior renovations. The building was last fully restored in 1979, when it reopened as a short-lived Chinese-language movie and theater venue. Since the 1980s, the Trocadero has operated as an independent club and concert hall.

The city's Chinatown Friendship Gate straddling 10th Street grew out of a joint venture between the city of Philadelphia and its Chinese sister city of Tianjin, spurred by the efforts of the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation. Assembled by 12 of China's finest artisans, the 40-foot gate was completed in 1984 and repainted in 2008.

Sources:

1. Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

2. Davis, Carolyn. "Face-lift for Friendship Gate - Five artisans have arrived from China to restore the weathered, peeling Chinatown landmark to its former brilliance." Philadelphia Inquirer. 26 Jul. 2008: E01.

3. Williams, Edgar. "A gateway from the homeland." Philadelphia Inquirer. 2 Dec. 1983: B07.

Original photo: Blanck and R. Carollo. "Department of Public Property-41202-0." 1960. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadephia Department of Records. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=143811.

Sources:

1. Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

2. Davis, Carolyn. "Face-lift for Friendship Gate - Five artisans have arrived from China to restore the weathered, peeling Chinatown landmark to its former brilliance." Philadelphia Inquirer. 26 Jul. 2008: E01.

3. Williams, Edgar. "A gateway from the homeland." Philadelphia Inquirer. 2 Dec. 1983: B07.

Original photo: Blanck and R. Carollo. "Department of Public Property-41202-0." 1960. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadephia Department of Records. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=143811.

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

Then and Now: Northwest corner of 2nd and Market Streets, Philadelphia

One of the most important consequences of the City Beautiful movement was an enduring affinity among city planners for open spaces, grand axes, and vistas, which lasted well through the 20th century. Aesthetic preferences, however, tend to be poor justifications for massive and costly urban renewal projects within democratic societies. Thus, 20th century planners developed alternative methods of selling their ideas. Just as "insalubrity" became the ostensive target of Parisian renewal schemes, "fire protection" obtained great currency in Philadelphia.

In the 40s and 50s, the protection of national monuments against the risk of fire became a chief justification voiced in favor of the complete clearance of whole city blocks around Independence Hall and nearby sites. In the name of fire protection, the National Park Service demolished around 1960 this row of commercial buildings between Christ Church and Market Street. Fire protection is surely a very legitimate concern when it comes to buildings of historical significance like Christ Church. However, few people today would find it an entirely rational justification for the razing of an active city block.

The northwest corner of 2nd and Market has now been an enclosed pocket park for half a century. The park space itself is rather pleasant, if not somewhat underused, and it certainly does improve the church's visibility from the south. Nonetheless, the cumulative effect of the excessive presence of grassy "firebreaks" around Old City's landmarks seems to present visitors with a misleading vision of a colonial city that does not feel particularly urban.

Further reading: Greiff, Constance M. Independence: The Creation of a National Park. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1987.

Original photo: Cuneo. "Department of Public Property-37331-0." 1959. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 15 Mar. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=140645.

Friday, March 12, 2010

Then and Now: Northeast corner of 4th and Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia

Constitution Place was one of the earliest projects of Philadelphia's post-war modernist construction boom, built in 1956 over the remains of four mid-19th century commercial buildings on what was once the city's "Banker's Row." Construction of the 13-story office tower also coincided with the beginning of large-scale demolition on the south side of Chestnut Street leading up to the construction of Independence National Historic Park.

More recently, Constitution Place hosted a key player in Philadelphia's restaurant renaissance; since 1998, it has housed Stephen Starr's ever-popular Buddakan restaurant.

Source: Walsh, Thomas J. "Constitution Place turnaround is done." Philadelphia Business Journal. 16 Apr. 1999.

http://www.bizjournals.com/philadelphia/stories/1999/04/19/newscolumn3.html.

Original photo: Mallis, Atheniasis T. "Public Works-42512-1." 1954. Philadelphia City Archives. PhillyHistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 23 Feb. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=99155.

Friday, March 5, 2010

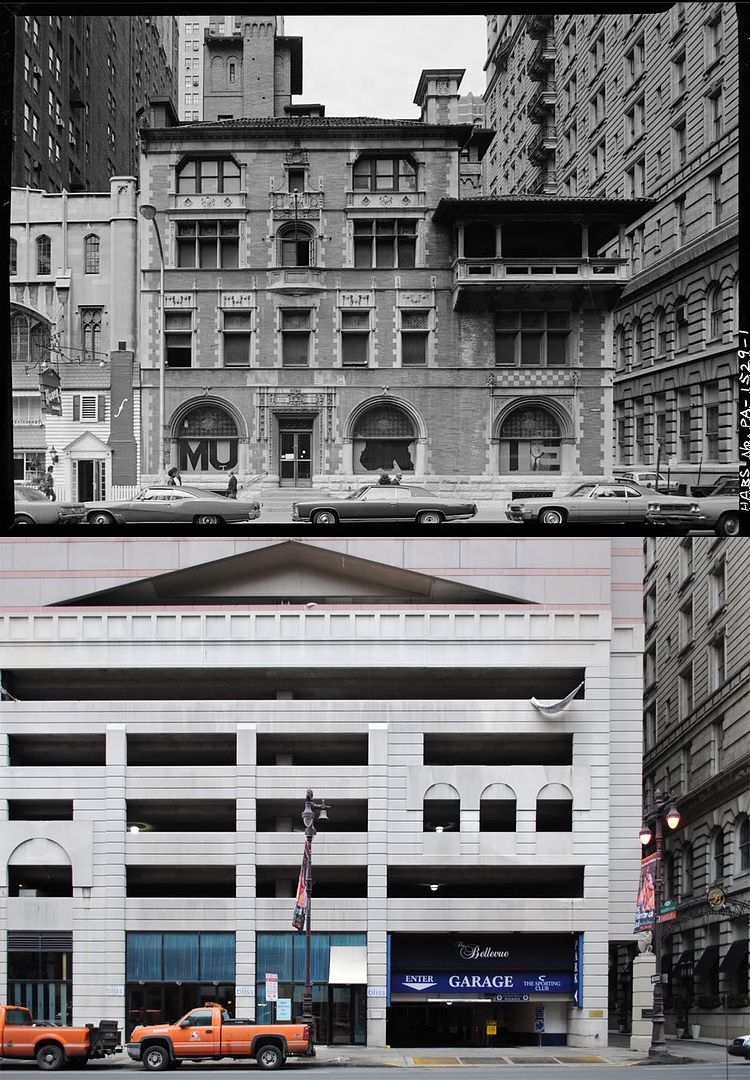

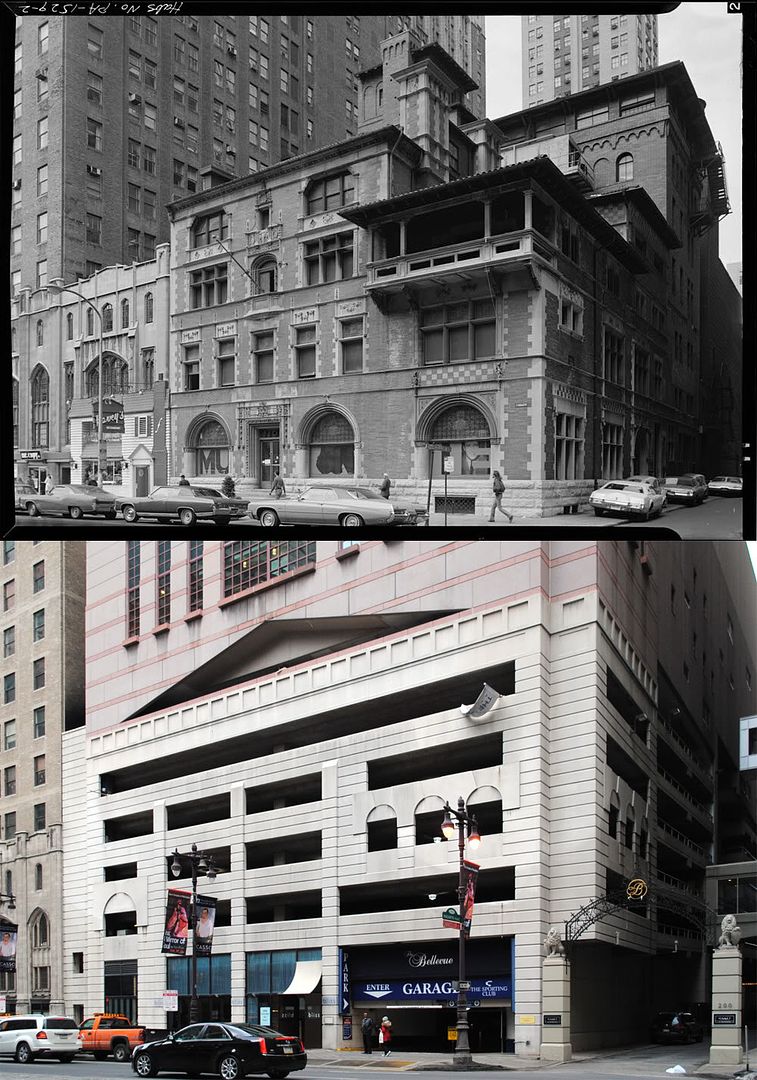

Then and Now: The Philadelphia Art Club, southwest corner of Broad and Chancellor Streets, Philadelphia

1972-2010

1972-2010When the Philadelphia Art Club formed in 1887, it purchased a former residence at 220 South Broad Street (at $100,000) for the establishment of its club house. Finding the existing building unsuitable for its needs, the Art Club organized an architectural competition, ultimately won by the 27-year-old Frank Miles Day. The renovated and expanded building opened in late 1889 sporting a new Italian Renaissance Revival facade. At the time, the New York Times described it in glowing praise as "one of the most beautiful and artistic clubhouses to be found in the country." In addition to the requisite galleries and parlors, the 5-story building also included for its members a billiard room, cafe, and library, as well as apartment suites and servants quarters. The club house was expanded with a rear "tower" addition in 1907.

During the 1980s, the firm of Richard I. Rubin & Co. took control of the redevelopment of the entire 200 block of South Broad Street, leading substantial interior renovations to the Broad & Locust tower and the struggling Bellevue Hotel. As part of their efforts, six-story parking garage was built in 1983 on the combined site of the former Art Club and the gothic revival Locust Street Theater. At the time, the development team also gave assurances that the garage would blend in with its neighbors and "not look like a garage." I will leave the final verdict to the reader's discretion.

In 1988, the Bellevue opened its new luxury sports club facilities in a new structure built on top of the parking garage. Interestingly, this pink vertical addition is a little-known work by the very well-known postmodern architect Michael Graves, and his first work in the city of Philadelphia.

Sources:

1. Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

2. "Philadelphia's Art Club - First Meeting in its New Quarters." The New York Times. 8 Dec. 1889: 6.

3. Byrnes, Gregory R. "Owners See Garage as a Boost for Bellevue." The Philadelphia Inquirer. 31 Oct. 1982: C08.

4. Hine, Thomas. "Graves Hired for Bellevue Project atop Garage - is the Architect's First in Philadelphia." The Philadelphia Inquirer. 11 Aug. 1986: E01.

5. "Philadelphia Land Use Map, 1942." Library Company of Philadelphia. Philadelphia Geohistory Network. Athenaeum of Philadelphia. 3 Mar. 2010. http://www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/view-image.cfm/LUM1942.Title.

6. "Philadelphia Land Use Map, 1962." Free Library of Philadelphia Map Collection. Philadelphia Geohistory Network. Athenaeum of Philadelphia. 3 Mar. 2010. http://www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/view-image.cfm/LUM1962.Title.

Original photos:

1. Boucher, Jack B. "PA-1528-1: East (Front) Elevation." 1972. Historic American Buildings Survey. American Memory. The Library of Congress. 25 Feb. 2010. http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa1000/pa1052/photos/138215pr.jpg.

2. Boucher, Jack B. "PA-1528-2: East (Front) Elevation, from northeast." 1972. Historic American Buildings Survey. American Memory. The Library of Congress. 25 Feb. 2010.http://memory.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa1000/pa1052/photos/138216pv.jpg.

Monday, March 1, 2010

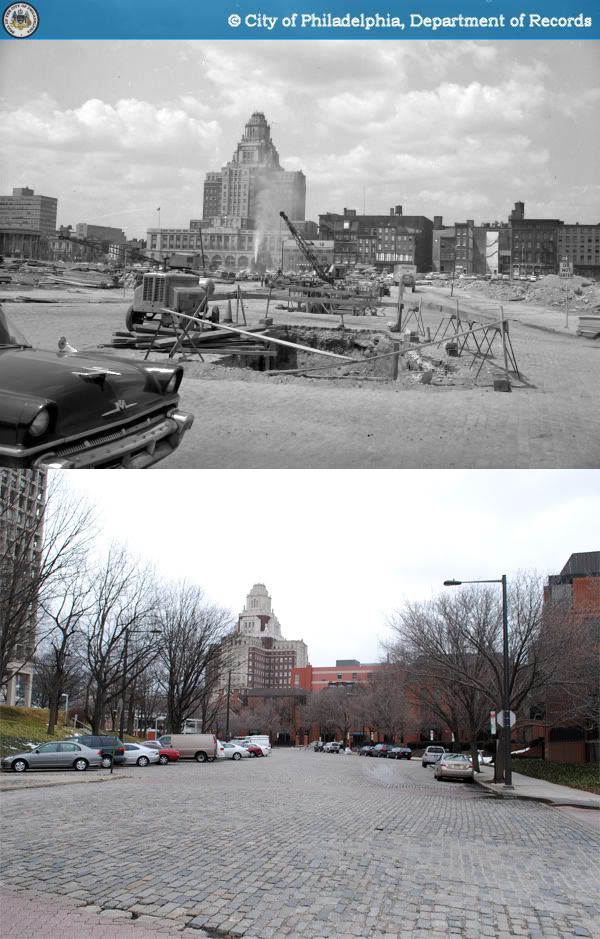

Then and Now: Dock Street northwest of Mattis Street, Philadelphia

1962-2010

(continued from previous post)

Dock Street's 100 block was rebuilt in two phases after its demolition. The rubble had barely cleared when the I. M. Pei-designed Society Hill Towers (1964) began to rise, set back from the street on an artificial hill. The triangular lot on the opposite side of Dock Street remained a surface parking lot for two decades before the opening of the Sheraton Society Hill Hotel in 1986, developed by regional mega-developer Willard Rouse.

Modernist urban renewal wasn't particularly keen on complexity or historical context. In their eagerness to "preserve" Society Hill as a refined, leafy, residential neighborhood, city planners chose to honor one peculiar vision of the colonial city that was oddly enough devoid of any serious commercial activity. Perhaps it was due to a bitter recognition that Philadelphia's time as a manufacturing powerhouse was over that the city's urban renewal efforts seemed particularly intent on eliminating all traces of the city's mercantile and industrial heritage. The photograph below, taken in 1961 from Front and Spruce Streets, gives a pretty good idea of the enormous amount of demolition needed to build Society Hill as we know it today.

Which probably makes Dock Street's fate all the more unfortunate. Its great width once made it a critical transfer point for goods coming into the port of Philadelphia. Now severed from the Delaware River by I-95, having lost all of its former street wall, today's Dock Street has also lost much of its reason for being. Unknowing visitors who now stroll along its wide, curving, Belgian block path could be easily forgiven for their bewilderment as to why it exists, seemingly outside of any meaningful context. If they were shown a few pre-war photographs, they could also be forgiven for their shock and disbelief.

Source: Bymes, Gregory R. "Rouse planning more hotels in Center City." Philadelphia Inquirer. 4 Dec. 1985: E01.

Photographs:

1. Widdop. "Historic Commission-47668-0." 1962. Philadelphia City Archives. Phillyhistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 27 Feb. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=107111.

2. Widdop. "Historic Commission-44551-0." 1961. Philadelphia City Archives. Phillyhistory.org. Philadelphia Department of Records. 27 Feb. 2010. http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/MediaStream.ashx?mediaId=10573.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)