Having endured 50 years of Japanese colonial rule from 1895 through 1945, Taiwan retains perhaps the most extensive collection of Japanese imperial-era architecture outside of Japan. To this day, many of Taiwan's national and local government institutions still operate out of the grand edifices built for Japan's colonial administration, including the iconic Presidential Office Building and the National Taiwan Museum, pictured above. These monuments of imperialism miraculously survived the nationalist anti-Japanese fervor that swept through Asia at the end of Japanese occupation and led to the destruction of most of their counterparts in China and Korea. Today, they are generally acknowledged as an integral part of Taiwan's architectural heritage.

Unsurprisingly, the strong European influence upon all levels of Japanese society during the imperial period made itself evident in its architectural practice as well. Quite naturally, the Japanese turned to European technology and design aesthetics for the construction of the grand bureaucratic monuments befitting a modern, nationalist state, of which they had no true domestic precedent. Consequently, most Japanese imperial architecture in Taiwan can be identified as variations on a number of architectural styles popular in Europe during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including French Second Empire, Gothic Revival, and Renaissance Revival.

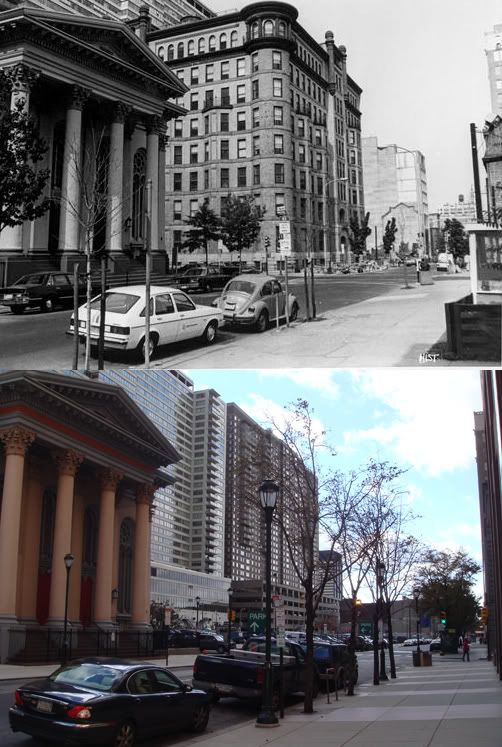

Recently however, I have become more interested in the more everyday commercial architecture built during the colonial era - the two, three, and four-story buildings that once lined Taipei's old streets. The pictures in this post were taken around the Zhongzheng District (中正區), in the area between Taipei Main Station and the wide boulevards of Taiwan's government center, which was the city's commercial core for the first half the 20th century. Its colonial-era commercial rows, not built for air conditioning units, backlit commercial signage, or the density demanded by Taipei's post-war population boom, have been nearly entirely replaced after successive generations of rebuilding.

Unfortunately, most remaining colonial-era commercial structures in this part of town seem to have been especially neglected, and have been largely unaffected by the preservation efforts that have created "heritage streets" in other parts of the country. Those that do remain standing also seem to have been built closer to the middle of the century, as they have little of the Victorian, neo-Baroque flourish that Japanese colonial architecture is best known for. I even managed to find a rather rare specimen of Art Deco in the bunch:

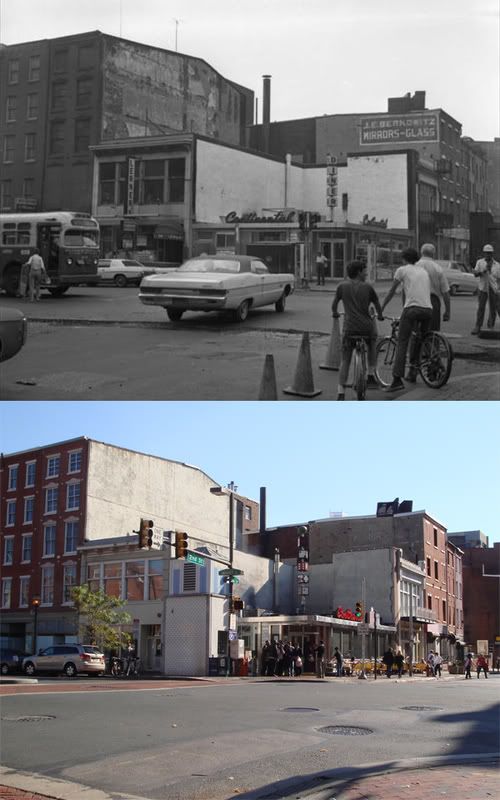

Sadly, a good many of them have also been altered beyond recognition by unsympathetic renovations. In a most perverse and extreme case, this last building was literally sliced in half, and further suffered a drastic alteration to its first and second floor fa

çades.

On Christmas Day, the Taipei Rapid Transit Corporation opened the gates at Nangang Station, the newest addition to an elevated and underground rapid transit network which now includes 70 stations. Nangang is the temporary terminal on the Nangang Line's extention, which upon completion next year will connect the district's growing high-tech office cluster and Exhibition Hall to the city's metro system. As a regular user of public transit in the United States, it is incredibly refreshing to travel to another place where public transit seems to be in a consistent state of growth rather than stagnation, and doesn't operate under the constant threat of budget and service cutbacks.

On Christmas Day, the Taipei Rapid Transit Corporation opened the gates at Nangang Station, the newest addition to an elevated and underground rapid transit network which now includes 70 stations. Nangang is the temporary terminal on the Nangang Line's extention, which upon completion next year will connect the district's growing high-tech office cluster and Exhibition Hall to the city's metro system. As a regular user of public transit in the United States, it is incredibly refreshing to travel to another place where public transit seems to be in a consistent state of growth rather than stagnation, and doesn't operate under the constant threat of budget and service cutbacks. Up until roughly a decade ago, land in this area of Nangang was largely dedicated to agricultural and light industrial use. Though the area in the immediate vicinity of the station is sparsely populated, the station seems to already receive a fairly steady stream of users, probably since it is still one of the only stations that serves any portion of Nangang.

Up until roughly a decade ago, land in this area of Nangang was largely dedicated to agricultural and light industrial use. Though the area in the immediate vicinity of the station is sparsely populated, the station seems to already receive a fairly steady stream of users, probably since it is still one of the only stations that serves any portion of Nangang. I was happy to see that the station is better designed than the older stations on the Nangang Line, most of which are rather austere and indistinguishable. Here, the standard grey ceramic tile floors are supplemented with cool stone stairwells, and the walls and ceilings are fitted with light green color scheme (especially refreshing in a city enamored of grey and light pink). Furthermore, the station includes an unusually large amount of public art in the form of murals, which all seem to have been done by the same artist. One installation in particular, the mural of chairs pictured below, is quite a hit with families with children.

I was happy to see that the station is better designed than the older stations on the Nangang Line, most of which are rather austere and indistinguishable. Here, the standard grey ceramic tile floors are supplemented with cool stone stairwells, and the walls and ceilings are fitted with light green color scheme (especially refreshing in a city enamored of grey and light pink). Furthermore, the station includes an unusually large amount of public art in the form of murals, which all seem to have been done by the same artist. One installation in particular, the mural of chairs pictured below, is quite a hit with families with children. While Nangang Station is pretty small as far as Taipei's metro stations go, it is quite successful at creating an open and inviting space for transit users. This is also helped by low and unobtrusive fare turnstiles, clear signage and lighting, open information kiosks, and ample indoor plantings.

While Nangang Station is pretty small as far as Taipei's metro stations go, it is quite successful at creating an open and inviting space for transit users. This is also helped by low and unobtrusive fare turnstiles, clear signage and lighting, open information kiosks, and ample indoor plantings. Of course, it would be un-Philadelphian of me not to compare this to SEPTA's underground stations, which fall woefully short of international standards. Near century-old structures are a problem, but it's still no reason to have stations that feel like Cold War bunkers. In fact, there are quite a few things that SEPTA could do without completely rebuilding its stations. SEPTA's fare collection modernization plan will in a few years present an amazing opportunity to replace bulky and unwieldy turnstiles with ones that feel less obtrusive and defensive. It would also do well to remove the mesh window barriers that cage in certain platform areas like those at 40th Street. And something as simple as maintaining year-round plantings could make a great difference, if SEPTA could get its employees to care. The list goes on, but the point is, for Philadelphia to have the world-class transit system it deserves, it will have to stop designing transit facilities that tell its users, "Keep out." Where the money to do this will come from is another issue entirely.

Of course, it would be un-Philadelphian of me not to compare this to SEPTA's underground stations, which fall woefully short of international standards. Near century-old structures are a problem, but it's still no reason to have stations that feel like Cold War bunkers. In fact, there are quite a few things that SEPTA could do without completely rebuilding its stations. SEPTA's fare collection modernization plan will in a few years present an amazing opportunity to replace bulky and unwieldy turnstiles with ones that feel less obtrusive and defensive. It would also do well to remove the mesh window barriers that cage in certain platform areas like those at 40th Street. And something as simple as maintaining year-round plantings could make a great difference, if SEPTA could get its employees to care. The list goes on, but the point is, for Philadelphia to have the world-class transit system it deserves, it will have to stop designing transit facilities that tell its users, "Keep out." Where the money to do this will come from is another issue entirely.